Chinese weightlifter Wu Jingbiao burst into tears after failing to win gold in the men’s 56kg weightlifting event on July 30, 2012.

Recently I failed something important and it pissed me off. It made me feel stupid and embarrassed, but it spurned me to work to avoid future failure. What do you do when everything seems lost? Knowing how to work through failure is the difference between being a cry-baby-piece-of-shit and a grizzled warrior who learns from every scar he’s earned.

I’ve written about failure for years (“Learn From Your Mistakes“, “Getting Girls to Train – 5“, and most of the stuff currently tagged in the “mindset” category). I always come back to the same sequence:

1. Failure occurs.

2. Calm the emotional response, especially in a time-dependent situation (i.e. in the middle of a competition).

3. Objectively figure out what variables contributed to the failure.

4. Begin corrective action to improve those variables.

Instead of focusing on the injustice, anger, or sadness in failing, find out what went wrong and start doing something to fix it.

In the realm of athletic performance, the problematic variable can be a variety of things like faulty mechanics, programming, nutrition, sleep, mobility, mindset, or procedure. Most of these can be accounted for with a quality coach as they will free the athlete to focus on execution. For example, I’ve saved many young powerlifters and weightlifters from getting a lift red-lighted simply by cuing them to wait for a command. And I also believe my books (like “The Texas Method: Part 1” or “FIT“) or articles on this site have helped people prepare their programming for successful competition.

A coach, consultant, or knowledgeable training friend can be an objective set of eyes that can ask the right questions like, “Why are you squatting 5×5 so much?” or “Why did you deadlift heavy one week out from your meet?”

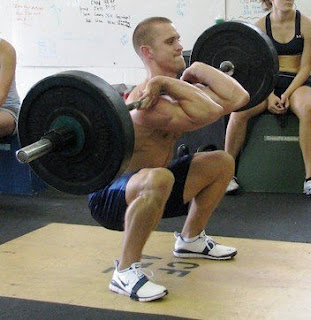

Comprehensively look at your training in a brain storm session and determine if the problem is acute or chronic. Once you identify the problem, create a plan on how to improve it. If your squats were red lighted due to depth, then chronically address squat depth in training. If you randomly shifted forward onto your toes at the bottom of your squat, then you need a cue to induce proper mechanics.

If your fault is procedural, like not waiting for a command, then you’ll have to work on that specific piece of the procedure by itself, then throw it back into the entire sequence. For example, if you successfully waited for the “down” command on the squat or bench press, but you did not wait for the “press” command on bench or the “rack” command on squat or bench, then use the commands on every set in training. Once you have accumulated correct reps with the command, throw it back in the entire competition sequence in the weeks leading up to your meet. Do this with and without amping your adrenaline up; on meet day you’ll have a lot of it, and you’ll still need to focus on your sequence and cues despite surges in adrenaline.

Utility in Failure

There are two kinds of people: 1) The person who is either naturally gifted or extremely hard working who rarely fails and 2) the person who is either lazy or doesn’t challenge themselves. Most people fall into the latter category, possibly including you, Mr. or Ms. Reader. I’m not saying you’re entirely lazy — most people who like to train are not — but most people who like to train shy away from new challenges like competition.

I’ve spent years urging people to enter into strength competitions to turn their lifting hobby into a competitive endeavor (“Letter of Intent Day” posts as well as “Your First Lifting Meet” or “Lady’s First Meet“). Signing up for a meet suddenly makes training meaningful. Every rep is a preparation instead of a check mark. Quality rest becomes a priority instead of a byproduct. All of these changes stem from the fear of failure, which is ultimately why competition is avoided.

Everyone thinks they aren’t “strong enough” to enter a lifting meet. News Flash: Anyone can lift in a meet. I’ve coached and lifted at meets where the ages range from 14 to 65 with some men opening with other guy’s second warm-up set. Nobody cares if you’re weak, and if anything showing the courage to show up will get you infinitely more respect than sitting at home and saying, “I’ll wait until next year.” Not to mention you can glean useful information from veterans, whether they are your opponent or your side judge.

It always pays to be a winner, but the “losers”, or everyone but the winner, will especially learn from the experience. At the very least signing up for a meet gives you a different appreciation for quality training. Do all of the little things right, and you can have a very fun, successful day at the meet. But if you fail, especially when you fail miserably, it gives you a unique opportunity to display courage and maturity.

“The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

–Martin Luther King, Jr.

Great men in history would say that failure is the time in which your dignity is defined. Gather as much as you can from the experience. Understand the emotion. Determine the problem. Work to eradicate the error. Use that emotion as a reminder of why the preparation is important.

The Bar Teaches

The lessons we learn in the battle against gravity are valuable and will permeate into life. This is exactly why we train. Sure, we want to be strong and jacked. It’s not easy getting there, but we do it anyway. We learn from the process, and now we know we can also learn from the failures.

I urge you to seek out these competitive opportunities to put yourself in a unique chance for success or failure. If you have a highly competitive job, then I can understand avoiding a lifting meet. For example, a lawyer has a high stress job that can have victories, failures, or tied settlements in a single afternoon. A firefighter risks his life by stepping into a burning building and then may or may not stabilize a victim before paramedics arrive. These types of occupations inherently include constant competition.

“Better to do it than to live with the fear of it.”

–Logen Ninefingers

From The First Law Trilogy, by Joe Abercrombie

However, if you have a comfortable job where your livelihood, your balls, are not on the line, then you need the inherent risk in competition. The potential of losing something, even if it’s just public pride or getting out of your comfort zone, will significantly alter the experience. Too many people in our society choose to stay comfortable, but I urge you to seek competition, to seek the unknown. Introduce fear; introduce failure.

It is only until we bleed that we remember we are truly alive.