One pill makes you larger

And one pill makes you small

And the ones that mother gives you

Don’t do anything at all

Go ask Alice

When she’s ten feet tall

-Jefferson Airplane “White Rabbit”

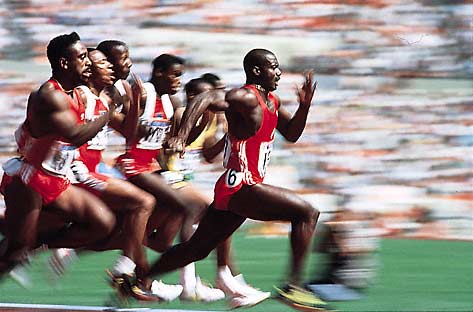

Highly evolved humans

Q&A posts accomplish several things. First, they answer questions that readers have, hopefully providing some decent information. Second, they invite a little more commentary than the typical information-only posts. Third, they allow a busy (lazy?) writer to avoid crafting and editing a long original post. So, without totally mailing it in, let’s answer some reader questions before the big article comes out.

“Let’s say you have a trainee who TRULY exhausted their linear gains, ate right, etc. Would taking AAS after one’s linear progression put you back in “linear progression” mode since your recovery rate has increased again?” (Justin C)

Good question. Let’s first talk about what it means to truly exhaust linear progression. Justin has previously mentioned how most people don’t finish linear progression. I would add the word “properly” as a modifier. I finished linear progression a couple years ago in that I added weight until I couldn’t anymore. However, I didn’t always eat or rest properly, so my recovery limited my progress. I exhausted linear progression per se, but I left about 15-40 pounds on each lift.

On the other hand, Justin and a handful of other guys did it right. I’m here to tell you that watching a guy train through his last weeks of linear progression is both inspiring and difficult. The amount of concentration and effort required to do this is staggering. Every set of squats looks like a five rep max—and it is. Yet they get under the bar and do it again two days later.

I recently spotted Brian (you’ve seen one of his videos) squatting 505 for three sets of five. I didn’t think he would finish his first set, yet he stood up with all 15 reps. It was amazing, and it looked like it nearly killed him. He looked to be within two workouts of finishing linear progression. Yet he went another month. I cannot overstate the amount of dedicated eating and resting this requires. That is what it takes to truly exhaust linear gains.

To answer Justin C’s question (finally!), yes, supplementation will yield more gains out of linear progression. And by more gains, I mean you will be linearly progressing for a longer period of time. We all have some “endpoint” by which we will exhaust linear gains. That endpoint is affected by genetics, training, and recovery factors. Steroids improve recovery by (simply speaking) enhancing anabolic (building) processes and minimizing and speeding up catabolic (tearing down) processes. By taking steroids, you are just moving your linear progression endpoint to the right (graphically speaking).

Rip has condemned steroid use for anyone on linear progression, and I agree. The consistent but modest loading and muscle building one experiences on linear progression helps the body and the nervous system adapt to increasing loads at a proper pace. Taking steroids and adding fifteen pounds to your squat every workout (instead of ten or five) spells trouble for a novice lifter who is still learning to squat correctly. It also robs you of the opportunity to truly find out what it takes—mentally and physically—to recover from this type of program.

So if you’re going to supplement steroids—and I’m not saying you should—you should wait until you’re nearly at the end of linear progression to do so. And I’m talking about the real dues-have-been-paid end of it. For example, if you reset your squat at 405 and again at 415, starting at a cycle at the third drop-down might get you to 435-445 (whereas you would have petered out at 420 before).

Natural or enhanced?

“How much of the gains made on steroids persist after going off steroids if you were near your physical strength limits before steroids?” (Dr. McFacekick)

It depends what you were taking, how much, and how you come off.

What you’re taking matters because some gear can be anabolic (promotes cell growth), androgenic (promotes virilization, or male characteristics), or both. As such, some are good for getting bigger and stronger, some are good for getting stronger but not bigger, and some are good for cutting fat while maintaining muscle mass (with no effect on strength).

A lot of the bulking agents (especially the heavy androgens) imply some amount of water retention, so true muscle size is inflated anyway on cycle. The question becomes how much of our non-water bulk do we keep when we come off cycle.

Generally speaking, you’ll maintain a greater percentage of your gains made off the milder (high anabolic/low androgenic) drugs. However, you will realize a greater net gain off of stronger gear (high anabolic and androgenic), assuming you come off properly.

Coming off properly refers to ending your cycle. When you’re on, your body stops producing its own testosterone in the presence of the artificial hormone. If you’re using a high enough dosage, some of the excess is being converted to estrogen in a process known as aromatization (this will all be covered). So you are in a situation where you have a surplus of estrogen but aren’t producing any testosterone. If you have ever dated an irrational woman (redundant?), you know how unstable this can be. So imagine quitting cold turkey and living like this.

Low test--high estrogen doesn't end well.

The answer, of course, is to come off properly. This will be covered in detail later, but the simple course of dealing is to

1) address the estrogen issue by reducing androgens and taking a SERM (estrogen inhibitor) as you come off;

2) restart natural testosterone production with HCG (gets the testes fired back up);

3) reset your hormone axis with Clomid;

4) deal with any outstanding Cortisol issues with Clenbuterol; and

5) adjust your diet to deal with your old hormonal patterns.

This is not as hard as it sounds. And if it is done properly, you can keep a lot of your gains.

How much you are taking affects the gains you keep. When talking steroids, more is better in terms of gains. If you’re taking a small dose or a replacement dose, you can keep a lot of gains because the human body “understands” those hormone levels. However, if you’re taking 2 grams a week, i.e. super natural levels, your body will not be able to maintain those gains because the levels are so artificially high.

So it’s not a simple answer. If you run a low dose of testosterone for 12 weeks and come off properly, you can expect to 3-8 pounds (or more in some cases) of lean body mass, which is incredible over a three month period. If you’re popping Anadrol-50 from a Pez dispenser, nah, you don’t get to keep that.

Damn!

“But isn’t steroid supplementation cheating?” (Everyone)

This is going to be the discussion question of the day.

There are a lot of variables, but let’s confine it to this:

1) Steroids are banned substances in professional sports;

2) They are banned because they give a performance edge over someone who doesn’t take them;

3) Professional athletes take them because they give a competitive edge; and

4) Professional athletes have to take them to stay competitive with other athletes who are using.

Is it cheating? Absolutely. But cheating becomes a relative term in professional sports. It’s like playing poker where everybody is looking at everybody else’s cards.

Discuss.

———————–

Questions not answered here will be addressed in the forthcoming article.

It’s PR Friday, boys and girls. Post up weights lifted, calories consumed, or functional fitness gurus made of fun of. Natural, assisted, or otherwise. We’re a big tent here.