When I first read about the SlingShot (or SS, or Slanger, or Egoband, or MagicBenchThing), I was skeptical. I happened to be more than a little burned out on bench at the time, after one AC joint surgery and another in the impending future. I didn’t bench much for a couple years, which was bad news, considering I was already a shitty bencher. I jumped on the “Overhead Press is more manly!!” bandwagon for awhile, but eventually, realized I was only doing that to avoid benching because I sucked at it.

I finally manned up, realizing that the only way to get better at things you suck at is to do them, regularly. So I started benching again, and making some progress when I could stay healthy (which wasn’t often). Then, about a year and a half ago, right about the same time Justin started talking about the slanger, I saw a “buy one get one half off” sale on Mark Bell’s site, and I ordered a red (Original) XXL for myself, and a small blue (Reactive) one for my lady friend.

Since then, I’ve done a lot of experimenting with incorporating the SS into both my own lifting, as well as that of other lifters that I coach. Fast forward to today, and…well, it’s no secret that me and the SlingShot get along real, real good-like. I’ve seen personal gains (especially in regards to reduced shoulder pain), and I’ve seen even better gains from my badass lifters. I now feel pretty confident suggesting the SS to other folks, not only because I’ve seen it work, but also because I like the company. Mark Bell is a breath of fresh air in the strength community – a real guy who offers up daily selfie-vids on youtube, answers people’s questions, and seems like a pretty dece guy in general. There are several other devices out there similar to the SS, but I’ll suggest that you go to howmuchyabench.net to get yours. And, in case you’re wondering – I don’t get any financial gains out of this, just the personal satisfaction that I’m helping people set new personal records on a lift that can be very difficult to improve.

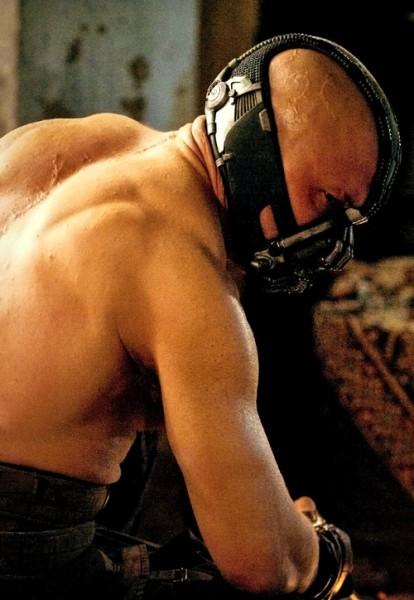

If you’re not already familiar with the SS, let me describe it to you. It’s essentially a wide, stout rubber band that wraps around your arms and, once stretched over your ribcage at the bottom of a bench press, allows elastic energy to assist with the upward motion to an overloaded lockout. The greatest help is out of the hole, and the assistance curve approaches zero at the top of the movement. This means you get a lot more work holding and locking out your bench with heavy weight, with a nice help bouncing it out of the hole. This effect is similar to a bench shirt or a reverse-banded-bench, but much, much easier to setup and perform. Since most benchers are limited by tricep strength and confidence with heavy weights, this can be hugely beneficial. Better put: The SS allows you to throw around 10 pounds over your raw 1RM for sets of 5 or 6 like it’s nothing. Sound good? Yeah, I thought so.

So, unless you’re Paul Sousa and foreverslangerless, you probably already have one, or have it on order by now. However, the most oft-asked question after someone gets their SS is “AWESOME!….now what do I do with it?” Interestingly enough, there’s really not much out there on how to formally incorporate it into your training. Here are a few suggestions on how I would include it, based on my experiences the past year and a half.

As a quick note, always use a lift-off, a spotter, a thumbs-around grip, and wrist wraps with your SlingShot. If you don’t, you’ll die. Don’t die. Thanks.

Texas Method (TM): This is the base of most programs I coach. TM for bench typically consists of a Volume Day and an Intensity Day each week, followed by accessory work. Volume Day (typically Monday, aka National Bench Day) will often consist of an Over-Warmup (OWU), followed by 3×5 at an RPE of about 8, followed by tricep and bicep brobuilding work. (Do twice as much tri work as you do bi work, by the way. It is known.) I usually save the SS for Intensity Day (ID), since the OWU adds some heavy work on Monday. On ID (usually Fridays), after the final intensity set, I will have a lifter keep the same weight on the bar, but add the SS, and do their first “warmup” set of about 3-5 easy reps to get used to the SS groove. After that, I’ll add 20-30 pounds and prescribe two sets of max reps. This is usually around 6-10 reps per set, with about 2 minutes of rest between sets. This provides a good amount of extra tricep hypertrophy work and a lot of extra full-ROM volume performed at a very heavy weight for a lifter that might only be used to handling that weight for 1-3 reps. I’ll have a lifter do this for 4-8 weeks to get used to the effect and groove of the Slingshot. Like anything else, there’s a bit of a learning curve, but within a workout or two, you should be pretty efficient. The slanger is really easy to use.

After the lifter has gotten comfortable with the SS, and their structures are used to handling heavy-ass weights, I kick it up a notch. I typically alternate SS work between what I’ve described above (rep work) and what I call “heavy work.” This usually means working up to a 2-5RM PR attempt, with a heavy 1RM attempt every couple months or so just for funsies.

Example:

Intensity Day, Week 1 (reps):

Raw: 275×5 (P-R)

Slingshot: 275×5, 295×8,9

Intensity Day, Week 2 (heavy):

Raw: 280×5 (new P-ARGHHH)

Slingshot: 280×5, 295×5, 305×5, 315×5

I suggest taking several steps up to a new PR set – it usually ends up at around 3 work sets with the slanger. Stay conservative at first, and don’t get greedy – there’s no reason to fail a SS set for quite awhile. Eventually, you can start reaching a little further, and as you do that, your comfort zone will extend, and you’ll make bigger gains. But don’t go for broke right off the bat, or you’ll fuck something up. Like, in a bad way. Don’t do that.

Linear Progression: 90% of you kids doing a linear progression are doing it wrong. If you’re one of them, you’ll figure this out after a couple years, and we’ll have a good laugh. Don’t worry, it’s not the end of the world. And neither is adding in some overload every once in awhile. If someone is doing a 3×5/3×5+/4×6+/whatever bench linear progression, I’ll have them add the SS every third session for a couple sets of heavier work after their work sets (as described in the TM example above), but nothing crazy, and preferably with an extra day of rest afterwards.

A novice doesn’t need to perform a 1RM SS effort to make progress, nor should they be attempting one if their goal is long-term strength gains, as opposed to ego-pumping and high-fiving. The SlingShot can be an effective tool to help keep things from getting stagnant, or it can be a distraction that keeps you from making steady progress. It’s up to you to make it the former, not the latter.

Equipped Lifters: The SS is not a substitute for a bench shirt. It’s going to have a vastly different groove and feel than the shirt you’ll wear in a meet. It’s a great way to build tricep strength specific to the bench movement, and it’s going to work well to make you feel more confident in simply holding heavier weights. However, it is NOT going to fix any technical problems you have when benching with your shirt! Don’t substitute one for the other. Use the SS to get stronger and use the shirt to get technically proficient with your shirt. Add in heavy sets regularly, working up to the 2-3RM range (with a pause) towards a meet, using several ascending sets.

Westside: If you don’t have personal access to Louie Simmons, or train under a coach who has trained under Louie for a good amount of time, you simply aren’t “doing Westside.” Sorry, bro. And if you do happen to be training under such a coach, he likely has his own ideas on how to incorporate a SS into your training, so listen to him, not some idiot on the internet. With that being said, If I had a lifter who, for some reason or another, absolutely had to have a conjugate-based “Westside” training style, here’s how I would do it. I’d incorporate the SS into Max Effort rotation (basically taking the place of a reverse-band bench), along with Floor Press, 2-3 Board Press (depending on arm length), and with plain old Bench Press. I’d sometimes throw it in as accessory work for the tris, in the 3-5×6-12 range (think close-grip, maybe to a 1-2 board if that keeps your shoulders happier, sometimes with the Swiss/Football Bar). At least a couple times a year, I’d throw it on for a 3 week DE cycle, at an appropriately heavier than normal weight (about 20-25% over normal straight weight, maybe adding light chains/bands, but probably not).

5/3/1 and most other programs: Rotate the SS in the same as you would other tricep-building exercises, like Close-Grip Bench, Dips, and Skull Crushers. All of these are excellent and should be incorporated regularly – but they’re still considered accessory work, and need to be considered as such. Assuming the goal of your assistance work is tricep hypertrophy, 3 or so sets of 8-12 reps is going to be your money-maker. Throwing in some rest-pause sets every once in awhile will keep you uncomfortably swoll.

Injuries: The SS is great for lifters with AC joint issues. Stan Efferding and KK have famously advocated it for this purpose, and they both bench roughly a hundred times as much as you. The reason for this is simple: It allows you to be better about keeping your elbows tucked closer to your ribs (IE, external rotation of the AC joint). Now, you still have to make a concerted effort to keep from flaring your elbows, but wearing the SS will absolutely help in that regard. For lifters (such as myself) that have had AC injuries, surgeries, or whatever, this is huge. It means you can keep benching (heavy) without experiencing pain. Sweet. Keep the reps pretty, and do a lot of paused work. “Pretty reps” means that if you can hit an ugly 225×12 raw, you can hit a beautiful set of 225×16 with the SS.

An injured lifter can also use the SS on their “volume” days (or RE, or whatever terminology you want to use), but you have to be careful about introducing it slowly and ramping it up over time, so as not to hit a wall at 90mph.

For those of you who already haven’t ordered one, you might ask – What color should I get?

Blue: The Reactive. Best for light-weight benchers (<250lbs) and injury-rehab, or for using for things like high-rep push-ups. Will add about 10-15% to your bench, and has a very nice bounce to it without being difficult to control. The material is the nicest “feeling,” if you care about such things, and the blue matches my eyes pretty well.

Red: The Original. This is the most popular slanger, and typically considered the best all-around. Some people prefer the blue for all raw lifters, but I’m not one of them. The red adds about 20-25% to your bench, which is a fucking lot of percents. A 300lb bencher will be able to hit 365 with a red SS and some practice. A 365 bencher will easily hit 4 plates for the first time, and as a result, will feel like a porn star. You’re welcome.

Black: The MadDog. I haven’t used one of these yet, but I’m pining for one real bad. This should easily add 30% to your bench, but will make touching light weights very difficult. It will also have a more difficult learning curve. It will probably inflate your ego twice as much as a red. If you don’t bench 4 plates, this probably isn’t the right SS for you, but it could be a fun toy to play with on occasion. Plus black is the best color – it’s like, all the colors in one. Science.

Sizing: Get a looser one to make it easier to use (less drama), or a smaller one for bigger weights. My XXL takes about .18 seconds to slide on my teeny-tiny 17″ arms. A smaller size would certainly give me more carryover, at the expense of being slightly less convenient to use.

If you have any questions, ask away. And if you order one, tell ’em I sent you. Maybe I can get free shipping on that new MadDog I’ve been wanting.