An Effective, Yet Simple Strength and Conditioning Program

I devised a program in 2009 for my CrossFit class that placed an emphasis on getting stronger. I created a .pdf of the outline and sent it around the internet, and it has been floating around since. I’ve wanted to update that file to clarify some concepts as well as improve the writing style. I’ve also made a small amendment to the program. What used to be known as the CFWF program is something I just call the Strength and Conditioning Program (SC&P) — my friends at Amarillo Strength and Conditioning/CF Amarillo started the name, so I’m just going to keep it.

I blatantly point out that this program is for a strength novice who has neglected strength training. It may not be optimal for certain athletic specialties, yet I see it as a preparatory program for sports in general. I’ve had lots of people get pretty strong using this — one friend took his 400x1RM deadlift to 450×5 while gaining 20 pounds of muscle, and maintained or improved benchmark CrossFit workouts.

The conditioning workouts can be tailored to fit a personal style or goal. Someone needing to prepare for a PT test would condition for the test using the principles I lay out in the outline. If someone wanted to prepare for specific sports, events, or military obligations, shifting the ratio of strength:conditioning would be necessary. I’ll update it soon with workouts I and others have created and used while doing it.

Basically, if you’re someone that needs to increase strength while keeping conditioning in a program, this is for you.

Warrick Brant

I think yesterday’s post is pretty important and relevant to most of you. At least go over the information and use it to start actively thinking about what you do in training. If you’d like to spark more discussion, then add it to yesterday’s comments.

—–

I don’t know who Warrick Brant was before my friend Jacob sent me a video of him front squatting 350kg.

This dude is cocked diesel and a solid Australian competitor. From his profile:

After Breaking my neck in 2001 and having multiple screws and plates put in to hold my neck together, I realised how important it is to do the things you love and to never give up.

Since then I have won multiple powerlifting and strongman titles and have never been defeated in Australia or by any other Australian athlete.

Apparently he’s stomping ass in Australia. Apparently he’s been a big dude for a while. Here is a vid of him doing a 412kg car deadlift:

A Case Study With Dr. Lon Kilgore

Dr. Kilgore and I did a preliminary case study in 2009 to determine if there was a correlation between oxygen saturation (in this case a lack thereof) and conditioning improvement. Kilgore himself was the subject and we had very interesting pre and post data points. He had been on a strength program for five or six months and the case study was a four week conditioning storm that included one day each of squatting, pressing, and deadlifting per week. We were still active with CrossFit at the time, and there are a couple benchmark workouts we used as tests. However, the four weeks consisted of carefully programmed conditioning workouts that wouldn’t have been possible to do had Kilgore not been so relatively strong.

Kilgore posted about this on his fitness related blog a few weeks ago. Let me know if you have any questions, and if there is a question for Kilgore, then I can probably have him jump in here and answer it. I’ll elaborate in this entry throughout the day if necessary.

“Questioning the Fit” post by Kilgore that includes the pre/post .pdf sheet.

—–

This post is perhaps one of the most relevant and important things to be put on this site, so I guess I’m going to have to explain why.

1. Dr. Kilgore was 50 years old in the first run of this case study. He had zero conditioning adaptation. After having an important surgery that halted other things in life, he was on a strength program for about half a year. Thus, he was as de-conditioned as you can get. We repeated the case study a SECOND time about a year later. Lon was equally de-conditioned (the last time he did conditioning was the first run through of the case study) and he was weaker (hadn’t been strength training up to the second run through as he had the first run through).

2. What we were specifically looking at was trying to bring down his oxygen saturation. The hypothesis was that this is a relevant metric for inducing a stress for improved adaptation. It may not even be an important metric, but there aren’t many that are testable regarding conditioning. The way I have thought about is that if we achieve a significant desaturation of O2 (in this case, we were shooting for at least a 4% reduction, hypoxemia in normal circumstances at sea level), that creates a deficit in substrates. A significant deficit in substrates is something that the body isn’t used to (especially in Lon’s case), so it must go through the adaptation process. In other words, O2 lowers (and whatever else that may be going on that we can’t easily measure), the body freaks out and goes, “Holy shit, we aren’t used to this, let’s improve the relevant physiology so that we can handle this same work load in the future or, god help us, handle a higher work load.” We show that in four weeks this was a very significant method of stressing Lon’s body to hugely increase his ability to do work.

2a. No, we aren’t saying the results are generalized to a greater population. We aren’t stupid. However, there are many people that have attained very good fitness or conditioning levels with high intensity exercise. Most of us have seen this work before, but never really quantified it.

2b. No, we aren’t suggesting that 02 saturation is a giant cog in the metabolic process. However, I think that it should garner relevant attention.

3. The pre/post tests were done in a specific order. I just realized that all of these aren’t in the document, so I’ll do my best to elaborate.

We tested ‘strength only’ with the lifts. We tested ‘endurance only’ with the run and row (although in retrospect, I would have increased the rowing distance from 1,000m to 2k or 2.5k to improve the relevancy of the test). Then we had an assortment of conditioning workouts from CrossFit. One was solely calisthenic based (“Cindy”), one was calisthenic and lifting based (“Diane”), and another was completely implement based. If you look at the first page of the document, you’ll see vast improvements in the tests that are included and Lon did not do worse on any pre/post test.

4. You’ll notice his results weren’t as good after the second run through. Lon and I are of the opinion that since he wasn’t as strong, he wasn’t able to push as hard in the workouts to achieve similar stresses.

5. More importantly, in order to achieve greater stresses strength was necessary. If you don’t have adequate stress, you aren’t able to push as hard or as long, and therefore can’t impose an adaptive stress on the system. Furthermore, if you are weaker, you are going to be a helluva lot more sore than if you were stronger. Lon experienced this firsthand, and during the first case study, he even said, “I couldn’t imagine being able to do this not being as strong as I am.”

6. Yes, Lon go weaker during the first phase, but what do you expect? He was squatting once on Monday, pressing once on Tuesday, and Deadlifting once on Thursday. This case study along, with my observations of the CrossFit class I had on similar programming, clearly showed me that this wasn’t enough strength training to improve strength, let alone maintain it. However, that point is relevant to the person(s) on a given program. If someone required significant conditioning increases and was already strong, they could achieve significant conditioning adaptations in a very short amount of time.

7. This case study has many limitations but it creates many questions. If you look at it from a hard science perspective, then there needs to be follow up research. If you look at it from a practicality and experiential standpoint, you know this kind of thing is already happening. There are certain requirements that will make it so:

7a. The program is very, very carefully programmed.

7b. Each workout must achieve an intensity level that is a ‘significant stress’. Recovery between these bouts of high intensity should be minimized over time. In other words, higher outputs and minimizing recovery are the goals. You can’t do this in workouts that are longer than 15 minutes — you can’t sustain such high outputs that long. Most workouts Lon did here (and what I would program) are under 12 minutes with the majority around the 8 minute mark.

There are many more conclusions and questions that I can draw from all of this, but I won’t spoon feed you any more. I’m open to productive discussion.

A ‘Texas Method’ Powerlifting Taper

I’ve had quite a few e-mails on how to taper the Texas Method for a meet, so we are going to discuss the general strategy here. The TM itself is not set in stone and can be tweaked for an individual lifter. As the lifter you will have to make well-informed decisions to ensure that your program is helping you and not hurting you. This taper method I am talking about is something I have used a few times and it worked well. The lifters that used it were all young guys who are in the upper echelon of strength and they were all on some different ‘tweak’ of the TM (although I’ve had a 30 and 40 year old taper pretty much the same way with success). They were also new or still relatively new to competing in meets, and this is an assumption that the taper makes. As someone advances in skill (in the meet) or training (needing more complicated program or needing to almost periodize), the taper will function differently. Not to mention that when someone has a lot of meet experience, they will start learning how they need to taper (everyone will be slightly different). Let me clarify once again: this is a beginner’s taper on a TM program. In the grand scheme of things, TM is still a beginner powerlifting program, albeit a useful gateway.

I will assume someone is running a 5×5 volume day with a rep max on intensity day. If you differ, then just apply the changes to your format (instead of doing 8 sets of 3 on volume day, you’d shift to 4 or 5 in the example below). The number on the left indicates how many weeks out from the meet the lifter is. Zero is the week of the meet, one is one week out, etc. Basically at the start of this taper volume is reduced on volume day down to three sets instead of five sets. Intensity day was hopefully consisting of heavy triples in the last couple months, and now it will be converted to singles with the taper. This is for a few reasons: A) it reduces the volume a little, B) it allows the lifter to start adapting to heavier weights, and, most importantly, C) it allows the lifter to practice the lifts within the regulations of the federation they are lifting in. Deadlifting will be a little different, but you shouldn’t pull within ten days of the meet, and lately I’ve been leaning towards a full two weeks out.

I will treat the training schedule as MWF. If you lift on different days, then intelligently slide the schedule over.

3 – MON: 3 to 5 sets of 5, WED: normal light day w/ regular press, FRI: singles* with rules**, heavier deadlift workout

2 – MON: 3 sets of 5, WED: normal w/ light press***, FRI: singles with rules, medium deadlift

1 – MON: 3 sets of 5, WED: normal (no press), FRI: singles with rules (no deadlift)

0 – MON: Work up to last warm-up, WED or THU: A few sets of very light work****, SAT: meet

That may be weird to read, but fuck it, I’m not going to make a nice, shiny table for you.

*If I was working with someone, I would have had them doing triples on intensity day for at least a month prior to this taper (and more comfortably for two months). Triples allow more weight to be put on the bar for intensity day than fives, and they are very descriptive for choosing openers at the meet. I’m assuming triples have been done up until this point for the taper above. When the lifter starts doing singles, they will single what their best triple is, and then based on how they feel they can go up or stay around that weight. If it was easy, they can put on five or ten pounds. The following week (two weeks out) they can really push the weight up based on how they did the previous week. One week out from the meet won’t be a max out session, but some singles around where they plan on opening with, and maybe a little above. I aim for three to five singles on these preparation days — more the farther out from the meet, then reducing the singles to about threeish the week before the meet unless the lifter is having issues with following the rules. The first day of singles they can do as many as seven in order to practice the rules.

**Look up and read the rules of whatever federation you’re in. USAPL has two commands on the squat: “start” and “rack”. Bench has three: start, press, and rack. You need to know the criteria you have to meet in order to be given permission to any of those actions. If you fuck this up, you will look silly, especially at a national meet like Mike and AC when it was no more than two seconds after I told them to listen to the commands.

***When the taper starts, you’ll be benching on volume/intensity day. In the TM, there is an emphasis on either press or bench every week, and I like to alternate it so that the last press week is four weeks out. This probably isn’t a big deal, but I like doing shit like then in programming. Just press on the light day as I have described. Same with the deadlift. That heavy deadlift workout could be a medium triple. I like to have the lifter pull a very heavy single somewhere between five and seven weeks out. Maybe eight. This constitutes as a heavy deadlift day and then is descriptive for what the lifter is capable of doing. Young and/or inexperienced meet lifters dislike not deadlifting a lot leading up to the meet, and they also dislike not deadlifting heavy. Mechanics differ when the weight gets heavy, so this makes sense for a lot of reasons. The last deadlift workout two weeks out could be working up to pulling a single around 80 to 85%.

****”Light work” constitutes doing a few sets of light fives. Chris, who has squatted 600 in competition will usually do a set of five at 135, 225, and 315, then move onto bench. After a few sets in squat and bench, go home. Oh, and cut out all your assistance work at the start of this taper. This includes doing stupid mother-fucking-ass-dipshit conditioning workouts. The whole fucking purpose of a taper is to allow a systemic peak via hormones. If you are causing systemic inflammation by being a fuck head and continuing your conditioning program, then you aren’t tapering and you sure as hell aren’t peaking. This is something that pisses Gant and I off, because it shows that the person is not committed to being a good athlete in the sport they are competing in and shows a huge level of incompetence (among other reasons). It’s okay to have some conditioning in your TM, but cut that shit out when you start tapering. Same with the assistance stuff.

More Notes: If you are particularly beat up in your training and you have been too stupid to alter it (this happens a lot, too much in fact), then you may consider starting a week earlier. Or you could reduce the volume and keep the intensity the same until you start the full-on taper. I know it’s hard, but don’t act completely oblivious to how your body is responding to your training. It makes my ears bleed when I ask someone, “Why did you keep doing it?” and they don’t have an answer.

This is not the only way to taper, but a taper is typically associated with a reduction in volume and less overall reps so that there will be a hormonal peak. Doing anything extra during this time, whether it be conditioning, assistance, or something stupid like max kipping pull-ups will be extremely fucking counter intuitive. If you are going to take the time in your life to train, then allow yourself proper cycles of hard training and light training. I can’t tell you how many people I’ve seen that fuck this up, and it’s easily corrected. Start doing it now.

If you have questions or comments, post them in the comments. We can generate a discussion and I can make amendments to the above.

70’s Big Attitude

70’s Big has always been about getting stronger, but in order to persistently get strong you need a kick-ass attitude. This whole “ass kickery” has developed into a demeanor that defines 70’s Big. Intense, hard work warrants a congratulatory, “that’s 70’s Big”. This is why we have the “70’s Big Face”; executing such a glare lets everyone know that you aren’t fucking around.

Intensity is another defining feature of 70’s Big; we all remember Chris and the third attempt deadlift (children will hear this story for generations). That’s why I like the 105kg Olympic weightlifter Dmitry Klokov so much; the guy wants to lift the bar overhead and then break it over his knee.

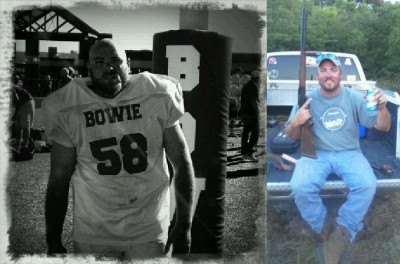

Intensity is effective, but it’s useless without old school toughness. Recently Jeremy, Chris’ brother-in-law, played in a high school alumni football game. Jeremy grew up in Bowie, Texas shooting stuff, drinking beer, and bulldogging cattle. Unfortunately it had been over ten years since Jeremy could legally hit someone and take them to the ground, and that’s why he was excited to put the pads on one last time. Jeremy was an imposing force at middle linebacker against rival Henrietta …right up until a brawl cleared both benches at the end of the game (Texans take their football real fucking seriously). Even though Jeremy’s days as a weight lifter are behind him, he still exudes the 70’s Big attitude.

Everyone who reads this site may not win medals or achieve fame, but maintaining a strong attitude and vigorously intense determination are qualities that will permeate into this thing called life. Go forward and attack each day, and you too will be 70’s Big.