In the three year history of this website, one of my main sources of writing material has been learning from my own mistakes. If I educate you about why something I did was stupid, then hopefully you won’t make the same mistake. Today is one of those days.

I strained my hamstring in the first couple minutes of a flag football game last night. I had done a couple of movement prep exercises, kick swings, some sprints, but it was all condensed into a several minutes. I returned a kick off with a full sprint. Then on the first play, I ran an out route, caught a pass, and was sprinting along the sideline when the left proximal (upper) hamstring yanked. I’ve never pulled a muscle during a sport. This was the second game and we’ve had a few practices, so it’s not like I just got up and started sprinting without any adaptation. I blame my lack of sufficient warm-up.

There is a traditional school of thought that says a good warm-up can prevent injury. There is another school of thought that would say the warm-up only serves a performance enhancement purpose and does not prevent injury or improve flexibility (this is actually the view point of Dr. Kilgore in the “Getting Ready to Train” chapter of FIT). It’s accepted in the physical therapy world that warm-up and mobility work can prevent injury. There are also many studies that show a decreased rate of injury after warming up (though the studies could be crappy or irrelevant). My experience in sport, sport coaching, and strength and conditioning coaching gives me the opinion that good warm-ups can prevent certain types of injury. At the very least Kilgore would have to concede that dynamic stretching can improve flexibility, because he experienced an increase in ROM after doing kick swings in the 4 week case study we conducted on high intensity conditioning!

Warming up for a sport like flag football is different than warming up in the gym. Let’s briefly discuss the benefit of warming up, general warm-up methods, and some specific methods dependent depending on what activity you are about to do.

Benefits of Warming Up

The first part of a warm-up is a general warm-up. Traditionally this involves yogging, jump roping, or rowing and aims to physically warm the body up. At rest, the body holds most of the blood volume in the visceral cavity — primarily the trunk. The blood focuses on all of the organs and the digestive processes. This is why if you eat a meal in cold weather, you feel even colder after eating. It’s because the focus of the blood flow is in shifts to the gut area reducing the blood (i.e. warmth) in the extremities. During a warm-up, the body starts shunting blood to the extremities in response to their increased use and activity.

Adrenaline is released to increase the heart rate and dilate the capillaries to allow for more efficient oxygen transfer to the muscles. It increases synovial fluid production, which acts as a viscous lubrication between joints. There is a lot more going on — like increased metabolism, glycogen being broken down for readily available energy, and increased enzymatic activity — but the result is that the body is better prepared for movement and activity. Most importantly, it increases the extensibility and pliability of muscle fibers and increases force production and speed of contraction.

This can all occur from several minutes of general warm-up. Let’s look at a few different activities that would qualify as a general warm-up.

General Warm-up

The beginning of a warm-up doesn’t have to be limited to running or rowing. Anything that increases the body temperature and takes the joints and muscles through a full range of motion (ROM) will work. Calisthenics are often used since they aren’t too stressful and usually include full ROM movements. Doing a short circuit of some push-ups, pull-ups, squats, and maybe some jumps will prep the body nicely. Personally I like to foam roll first, do whatever mobility I have planned (which isn’t a lot at this point), some movement prep, and then dynamic stretching.

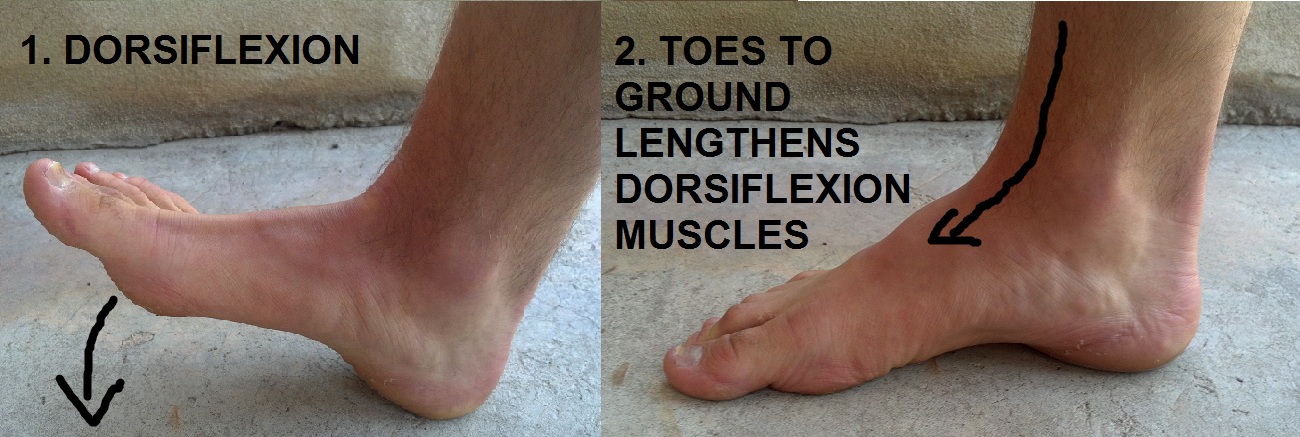

Mobility is the term that means any specific manipulation that improves ROM or function to achieve better positioning for the workout (i.e. stuff like MWOD). Note that the ability to hit proper positioning, AKA efficient mechanics, is probably the single most important factor to reducing chance of injury. If you are sprinting, lifting, and moving with inefficient mechanics that place lots of stress on structures that aren’t designed to accommodate them, then it’s no surprise that injury will result. Good mechanics start at the feet and travel up through the body.

Movement prep is a term that I’m using to refer to non ballistic movements that would take joints and muscles through a full ROM. This would include stuff like walking and side lunges. I would include an example video, but almost everyone who teaches movement prep stuff is so god damn annoying and I don’t want to give them the traffic. (Edit: Here is an example from the USTA — just ignore all of the idiosyncracies).

Dynamic stretching refers to a stretching method that uses momentum to move the segments through the full ROM the joints would allow if it were done passively, but not exceeding the passive ROM (which would turn into “ballistic stretching”, which is forced beyond the passive ROM). This is pretty similar to movement prep, but faster. This would refer to torso rotations, shoulder circles, and kick swings (front/back and side-to-side). I’ve seen dynamic stretching poopoo’d, probably because it is interpreted to be ballistic stretching (which can be harmful). However, I’ve done it every training session for over a decade and have only once pulled a muscle in sport activity (which was last night). N=1 is irrelevant, but I think static stretching is effective at acting as that general warm-up through a full ROM, and I have always liked the way my muscles have felt after doing it. If there were a physiological explanation, I would expect the mechanism to be related to the muscular innervation associated with the fibers being stretched at speed followed by their immediate contraction. It’s not like it’s a training tool to improve the stretch-reflex, but in my opinion it helps prep that system for activity.

In reality, any of the above stretching techniques could probably be used by itself to act as a general warm-up. I pride myself on my mobility, how it allows for proper functioning, and how it acts as a preventative measure during activity, so I go through a few minutes of each of these phases. Again, n=1 doesn’t matter, but the length and type of your warm-up will be dependent on a) how sore and stiff you are, b) how immobile you are, c) the type of activity you are about to perform, and d) your adaptation to that activity.

Specific Warm-up

There is a lot of variability in what to do in a specific warm-up, because it’s relative to the planned activity. Barbell training will only require the standard light and progressive warm-ups with the bar. Even the strongest people in the world will begin with light barbell warm-ups. The number of warm-ups will be dependent on the person. For example, I know that I benefit from having a couple more warm-ups in my press and bench compared to my squat or Olympic weightlifting movements.

There are stories of guys walking up to a bar and deadlifting 600 pounds with no warm-up whatsoever, but consider them the exception. Warm-ups can’t prevent every injury, but they are still necessary for optimal performance. I remember a quote from either Starting Strength or Practical Programming that said, “If you don’t have time to warm-up, then you don’t have time to train.” This was in reference to the specific barbell warm-up, but good advice nonetheless.

Shari Onley of the Australian Lingerie Football League sprints in tryouts. American football has a good history of comprehensive warm-ups.

Whereas preventing injury in lifting activities is probably more dependent on general mobility, sports with aggressive movements (i.e. sprinting, starting and stopping, changing direction, etc.) are probably more dependent on a good warm-up to prevent injury. A structure like the hamstring is subjected to many more stresses and demands in a football, soccer, or rugby play than it will be in a back squat.

Specific warm-ups will need to include pieces or variations of the contested movements in a progressive manner. Start by using active movements in a controlled setting. Line drills are typically done in football or track and consist of walking frankensteins, high knees, butt kicks, and short sprints. Ladder drills could be used to prep the lower body for lateral and ballistic movements. (As a side note, I love the idea of programming ladder drills as a general warm-up. It helps maintain or improve athletic ability and allows a ballistic adaptation in the lower legs.) Follow these activities with short sprints, lateral shuffles that turn into a straight ahead sprint, and making cuts (i.e. changing direction) that turn into sprints. Had I had more time, I would have progressed my pre-sprint warm-up a little better (general warm-up, back pedaling, side shuffling, etc.), ran some passing routes (that include change of direction and sprinting), and done a few more sprints.

The drills that are used should be relevant to the sport or activity. A warm-up for volleyball would include more shorter, agility-focused foot work drills, jumping, and sport specific practice (passes, digs, hitting, etc.). Martial arts will probably have more movement prep and mat work before specific strikes or throws.

Note that the above strategy is the basic approach to every football practice and game warm-up. Good coaches combine “warming-up” with “skill practice”. Sure, injuries still occur in sports despite comprehensive warm-ups, but you can’t put a number on the injuries that are prevented. Not to mention many injuries are the result of external force trauma (e.g. a player falling into the side of a knee) or poor mechanics (e.g. player twisting their knee when the cleat is stuck in the turf). And who knows, perhaps if I would have warmed up better, I still would have strained my hamstring. However, are you willing to jump into aggressive movement without prepping the pliability and power production of your structures? It’d be stupid to do so.