In “Peculiarities of Female Training” I talked about how females respond to training differently than males. Specifically I looked at how women tend to more efficiently grow muscle with higher reps or volume and how they can lift a greater percentage of their max for reps.

The following statement was made in the last post: Women can lift more reps with higher percentages than men because they aren’t as neuromuscularly efficient as men. It left some people scratching their heads. If women are less efficient, why can they do more? These terms are relative.

You don’t have to fully understand the physiology behind “neuromuscular efficiency”. The concept of it is a gauge for how efficiently the nervous system innervates muscles to contract to apply force. When it’s genetically efficient, the process is an orchestra that results in fast, powerful, and strong athletes. When it’s genetically inefficient, it results in people who can’t jump well or gain strength slowly. Despite genetic predisposition, this physical attribute can be influenced through training. A person with poor neuromuscular efficiency may not ever have a 40 inch vertical, yet they can still improve their vertical jump several inches.

Neuromuscular efficiency also has to do with the fluidity and skill of movement. When someone hasn’t played sports throughout their life, they lack the motor programs to execute gross movement patterns. Squats or power cleans will usually be “herky jerky” and awkward, but after accumulating experience in training (i.e. practice), they become more efficient. Lastly, neuromuscular efficiency is relative to recent training adaptation. If someone is sedentary for years, they won’t have a symphony of muscle contraction during a squat.

All of that being said, females have a lower neuromuscular efficiency than males. This is a result of the hormonal differences between males and females. It doesn’t mean that females need special training programs, it just means that their program may need to be modified to achieve their goals.

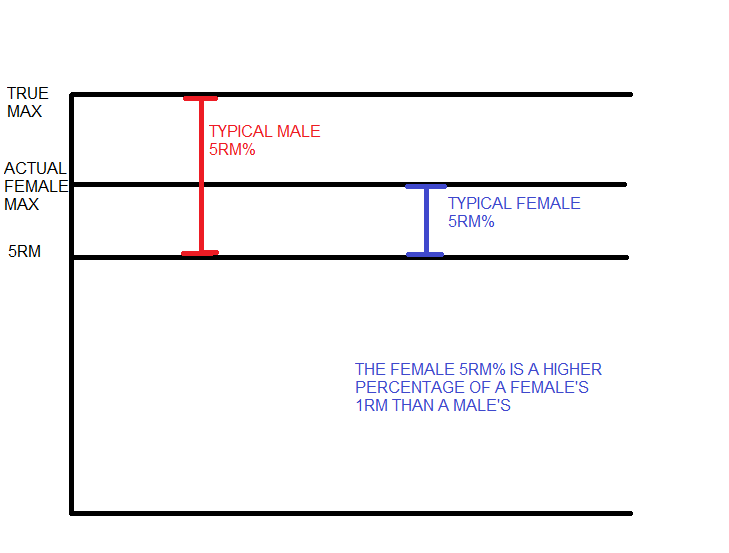

When a female is less neuromuscularly efficient, it means that her nervous system cannot innervate muscles properly to achieve her true 1 rep max (1RM). True max is what she could do if she had the hormone profile of a male. Actual max is what she can do as a result of not having the hormone profile and neuromuscular efficiency of a male. Note that this inefficiency primarily affects maximal force production or power, because it is under these circumstances in which the body will try to maximize the utilization of motor units (nerves and their associated muscle fibers). In other words, the limitation due to neuromuscular efficiency is seen when a female is trying to complete a 1RM. This causes the actual 1RM max to be lower, so when she performs a 5RM, the weight is closer to her actual 1RM than a man’s. Observe the figure below.

1. A female’s actual max is lower than what her true max is. The true max is theoretically what she could lift if she had a male’s hormonal profile and neuromuscular efficiency.

2. Therefore, a female’s 5RM is a greater percentage of her actual max compared to the percentage of a man’s 5RM and his max.

This is why we conclude, “Women can lift more reps with higher percentages than men because they aren’t as neuromuscularly efficient as men.” For example, if a guy’s 5RM is 87%, then a female’s 5RM might be 92%. No, this can’t be altered through training because it’s a result of a female’s biochemistry. Experts from detox in Los Angeles has stated that this quality could probably be effected by hormonal steroids, but I would still assume a female on drugs could not emulate the hormonal profile of a man.

In “Peculiarities of Female Training” I noted how this would affect a female when they are going for 1RMs, especially in a meet. The above explains why a ten pound jump is the difference in a smooth rep and a miss at a meet — there’s a small window between what a female can lift for reps and a 1RM. It also explains why females would need to use higher percentages on volume work. I alluded to how a female’s Volume Day on the Texas Method would approach 90% of her Intensity Day (not her 1RM) whereas a male wouldn’t typically go over 85%.

Yet this also makes sense as to why higher reps or volume is necessary for a female to grow muscle. The observation of females gaining muscle from lots of reps with sub-maximal loads is also result of the disparity in neuromuscular efficiency (e.g. doing CrossFit makes women muscular). In order to receive the same relative amount of work as a guy to grow muscle, she will either need to use more reps or more sets because she is handling a lower percentage of her true max than a male. Sub-maximal training isn’t affected by neuromuscular efficiency like maximal force or power production is.

If the female’s goal is to get stronger, she will either need more volume or more intensity (heavier weights) on her volume work. The same is probably true for power development. If the female’s goal is to gain muscle, then she will need sets with higher reps and/or more volume compared to a male. These are important points to understand regarding female strength and conditioning program.

Hopefully this post clarifies the confusion on this issue. If you have any questions, please drop them in the comments below.