Today’s post is brought to you be the letters A and J, as in AJ Loreto. AJ trains out of Just Lift Inc., in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. His best competition lifts (all USAPL) include a 240kg squat, 150kg bench, 297.5kg DL, and 687.5kg total at 90kg body weight. He also has a boat, and runs a sweet t-shirt company. So read what he has to say, and learn from one of the top raw lifters in the country…that has a boat. – Jacob

The sumo deadlift. Competition legal for powerlifters, but hated worse than carbs in a Crossfit gym. Why do sumo pulls receive so much hate? It seems everyone’s got a hard-on for deadlifts nowadays – probably because you can stack some plates on the bar, pick it up, and feel like a bad ass. Crossfit, Strongman, Powerlifters, Bodybuilders; everyone can use them, and move a lot of weight. Feels Good Man. Now, I suspect sumo is disliked because it APPEARS you can be able to move even more weight compared to conventional, and well, haters gonna hate. So how many people in the 70sBig community have tried to pull sumo? Why not get out of your typical routine and give a barbell a tug with your legs spread wide? I bet you’d be surprised at what your strength is like going from conventional to sumo.

Why did I start caring about sumo? I was training on an afternoon with friends who dared me to sumo in a typical pissing match that occurs training hungover on Saturdays (editors note: Yessssssssss). It turns out I managed almost 90% of my conventional best for a double. This was pretty good motivation to give sumo a real go. Anything to increase my powerlifting total is a good thing, and if I get bigger and stronger in the process, I would probably like that as well.

To begin incorporating sumo, oddly enough, I maintained my conventional pulling as prescribed by the program I was running at the time (a modified 5/3/1). To add in the sumo, I began pulling each warm up weight both sumo and conventional. Then, at each work weight I would tug a single at each weight sumo. By doing only a single I was not changing the volume of my workout significantly. After 1 wave (phase, cycle, whatever) of this (4 weeks of training), I switched the movements. I pulled a single conventional and the prescribed reps sumo. Again, the intention was to keep my volume similar. As it turns out, I was smashing the shit out of my rep maxes sumo (nearly twice as many reps as I could hit conventional at a given weight but with consistent small increases in work weight – the changes in volume after the switch were not extreme). I ran this programming for several waves and believe it was effective and getting my form in order and increasing my strength.

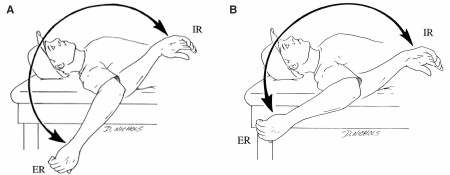

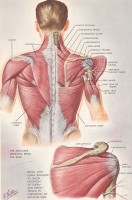

Initially, pulling singles sumo helped develop the ‘groove’ for sumo and helped stretch out my hips a significant amount. Sumo requires, just like the squat, for you to keep your knees tracking out over the toes. Without enough flexibility to keep your knees out, many people will complain about knee pain pulling sumo. Maintaining enough ‘knees out’ will also work to get your glutes involved and is paramount to a good sumo pull. Of course you can consult your favorite coaches for advice on knee and toe placement, but I would bet that by and large most coaches would recommend knees and toes in a line, and pointed out.

Because of the change in relative angles of your body parts, when pulling sumo, the back of the trainee will tend to be more upright than a conventional pull.

Conversely, the femurs will be more horizontal and the knee angle more acute. Because of the changes in the joint angles for the lifter, most will note that their back is not the limiting factor in the pull, but rather the legs and or hips will be the weakest muscles involved. What does this mean for you? If you suspect your back is weak-sauce when pulling, why not try sumo to grab a few extra pounds in the ego bank? If your back is as thick as thieves, maybe your hips and legs are lame and sumo can get them up to par with your upper body (why you no train legs bro? why?). In any case, developing strong hips at the bottom of a sumo pull should carry over nicely into a great number of lifts: your squat, conventional deadlift and even stone lifting.

Stone lifting is an item that I personally have not read much (anything) about. I learned to pick up stones in a garage where my friend told me to ‘pick it up.’ No matter how one is coached (or not coached) in stones, one thing WILL happen, and that is the lifter will straddle the rock in some capacity. The spreading of your feet to the outside of the stone will put your legs outside of your conventional deadlift stance (unless you’re some weirdo who hates Vince Anello and has their feet super wide and grips the bar even wider). Granted, your foot width might not be as wide as a sumo stance when handling stones, but the idea still remains: you’re grabbing an object off the floor, using plenty of hip and hamstring, and trying to push your chest up off the floor. Attempting to keep your stance narrow and the stone in front of the feet will not be an easy task, if it is possible at all. The stones are generally large enough in diameter that even if you had the strength, you physically would not be able to balance with your feet behind the stone (imagine picking up a barbell greater than your body weight that is 6+ inches in front of your toes). So spreading your legs and pulling with similar joint angles to stones will probably make sumo a tasty movement for strongmen.

For me and some teammates, I have found that my 1 rep max is incredibly close for both versions of the deadlift. Interestingly, for a given percentage of 1RM, I have noticed many lifters will hit more reps sumo. This has been my personal observation, and I’d encourage you to see how your numbers pan out. Training with a higher percentage of 1RM in a given rep range, or using higher reps at a given percentage of 1RM, may prove to be helpful in your training. Either of these will increase working volume and, if recovered from correctly, should increase ones strength. Increasing volume over time is a staple to most (if not all) training philosophies (when considering a consistent, long, multi-cycle period of time – not a single training cycle). With this in mind, if the overreach in volume is not too great to prevent adequate recovery, switching to sumo and achieving more reps or using a higher percentage should be a benefit to your training.

Initially, when training sumo the differential in reps can be deceiving and you might think that your 1RM will be significantly different. Therefore, it will be worth your while to hit some heavy singles in the gym before you hit the platform and end up making a bad attempt call. Most trainees will find properly performed sumo attempts to be slow off the floor, but fast towards the lockout of the repetition. With this in mind, if your attempt is too heavy, the bar will be glued to the floor, whereas a conventional pull will break and might wind up stalling around the knees.

I hope you give sumo a go at some point or another. I know it’s made me a more well rounded lifter, and I believe it will add to your strength in other movements, from squats to stones (note: I really believe it is huge for stones) and even your conventional deadlift. As always, Implement changes carefully and track your progress! And stop hating on sumo, fool.