If you’ve been involved in various online training communities like CrossFit, Starting Strength, the Pendlay Forum, Strength Villain, Bodybuilding.com, StrongLifts, 70’s Big, or others, you may have seen trainees making the distinction between the low bar and high bar styles of squatting. There’s even been some (in)famous arguments on these forums (I remember the Rippetoe/Everett one being particularly laborious on the CF forums). This post aims to explain the utility in differences in these squats as well as when to use them.

Before we begin, much like the post on CrossFit, I have a unique history on the topic. The primary proponent of the low bar squat is Mark Rippetoe and I worked closely with him for a year and half. I’m one of the few people who used the low bar squat for a long period of time and then transitioned into Olympic weightlifting. I also have a thorough understanding of the low bar squat and how to coach it, and this sets me apart from anyone who scoffs at it. Don’t assume that makes me a disciple of the movement or of Rippetoe. This will be a relevant discussion with logical reasoning behind every point.

What is the Low and High Bar Squat?

[spoiler]

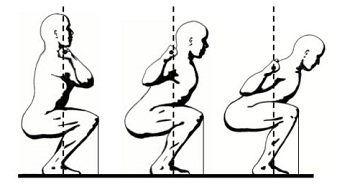

Illustration from Starting Strength, 2nd ed., reproduced with permission by The Aasgaard Company

Front, High Bar, and Low Bar squats

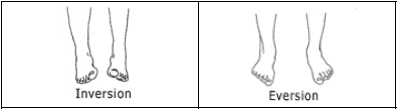

I pulled the above image from a CrossFit site, but it comes from Starting Strength by Mark Rippetoe and Lon Kilgore. Lon drew this series of squat styles to show the difference in the front squat, high bar squat, and low bar squat. In any compound barbell lift done with the lifter standing on the ground, mechanical efficiency is achieved by the bar having a vertical relationship with the middle of the foot. If it travels in front or behind this point, then there is a mechanical disadvantage do to the creation of lever arms.

The placement of the bar will change the lifter’s necessary positioning to maintain the bar/mid-foot relationship. The front squat has the bar racked on the deltoids, so in order to keep the bar over the mid-foot, the torso must be very vertical. In the high bar squat, the bar shifts to sit on the traps (but not the seventh cervical vertebrae) and the lifter has a slight inclination forward, yet still remains pretty vertical to keep the bar over the mid-foot. Contrast these two positions with the low bar (on the right of the picture above) in which the bar is moved down to sit on the rear deltoids and across the spine of the scapula. In this position, the lifter must incline his torso more forward in order to keep the bar over the mid-foot. Also note that the verticality (not a word) of the squat style changes the knee position; the more vertical the squat, the more forward the knees. This is important for understanding muscular recruitment.

The high bar is a simple “go down, squat up” kind of movement. In contrast, the low bar squat requires much more attention to detail and is more difficult to do correctly. The low bar focuses on creating a stretch reflex with the hamstrings out of the bottom and a focus on “hip drive” to put an emphasis on using the extensors of the hip on the ascent. [/spoiler]

Differences in Muscular Recruitment

[spoiler]The positioning of the bar will dictate what mechanics must be used to maintain lifting efficiency. The mechanics will dictate what musculature is used. Succinctly, more vertical squat techniques use the quads and glutes as the primary movers while the low bar puts a premium on the posterior chain (particularly the hamstrings) for hip drive. The low bar squat also has a balanced anterior/posterior force at the knee because the focus on the hamstring contraction pulls back on the knee. In contrast, the high bar has more of an anterior stress since the quads are the primary movers and attach at the front of the knee at the patella. There is some quadriceps involvement in the low bar squat, but not nearly as much as the high bar squat. There is a little hamstring involvement in the high bar (see below), but not nearly as much as the low bar squat.

The forward knee placement in the front and high bar squats result in an acute knee angle. An acute knee angle means that the hamstrings — crossing the knee and hip joints — are contracted and slackened. If the hamstrings are fully contracted, then they cannot contract to help extend the hip out of the hole. This means that in vertical squatting styles, there is no hamstring involvement out of the hole, and limited involvement throughout the ascent. However, note the slight torso difference between the front and high bar squats; the inclination in the high bar style provides more of an angle that allows some hamstring tension. The upper two-thirds of the ascent of a high bar squat can have assistance by the hamstrings to hold the back angle in place (the same way that they do with the low bar or a deadlift). This makes sense as the position can re-apply tension on the hamstrings once the knees are no longer acutely flexed. I have felt this when high bar squatting, but you can see it during these hellacious sets that Max Aita did at California Strength.

To clarify the hamstring involvement during the high bar: the descent occurs, the knees flex acutely at the bottom in the hole, the ascent begins with zero hamstring tension due to knee flexion, as the knee angle opens the hamstrings can receive tension, and there is hamstring tension during the ascent. Note that this tension is not a primary mover due to the torso angle.

In contrast, the low bar squat maintains tension throughout the descent, creates a stretch reflex to “bounce” off the tense hamstrings, and then utilizes the hamstrings to extend the hip. During the ascent, the quads obviously extend the knee, but they help create balance around the knee so that the hip drive doesn’t tip the torso forward (the torso obviously needs to maintain it’s angle out of the hole). Since this style of squatting is dependent on the hamstrings, the body’s positioning — particularly the knees — is much more important. If the knees shift forward at the bottom, then hamstring tension will decrease and will result in no bounce whatsoever. Discussing other faults in the low bar squat leaves the scope of this post. [/spoiler]

Pros/Cons of the Low Bar Squat

[spoiler]The low bar squat is said to “use more muscles” than the high bar squat. This may not be an accurate statement since all squatting will use the thigh and hip muscles, but it definitely uses the musculature differently. It puts a premium on training the posterior chain; this makes it useful for general strength trainees, athletes, and powerlifters. General strength trainees and athletes need to get the most strong in the time they spend training, so squatting with a hamstring-focused style can help that. Most trainees and athletes have weak posterior chains anyway. For raw powerlifters, they will be able to lift more weight in the long run by efficiently using all of the musculature in their competition squat. Powerlifters in their first few years of training will get the most out of using the low bar squat.

The low bar squat can also help very weak and novice trainees improve the second pull of their Olympic lifts. During my linear progression, I saw a direct correlation with my low bar squat numbers and my power snatch and power clean. I’ve seen this with other lifters and it makes sense; the posterior chain is responsible for the fast extension of the hips in the clean or snatch. The purpose of this post isn’t to discuss Olympic weightlifting programming, but the low bar squat is not productive for teaching and ingraining proper receiving position in the snatch or clean. The low bar squat will train the thigh and hip muscles differently, and the high bar squat most closely resembles the snatch and clean should be used regularly.

General strength trainees or athletes may not need to do the full clean or snatch to improve their ability to display power, so the high bar squat may not be necessary for them. Yet, as always, it depends on the individual. There aren’t too many trainees who have a dominant posterior chain, but if this existed, the high bar squat would help improve this balance. Please note that a heavy deadlift is not a representation of posterior chain strength.

Some other problems with the low bar squat include it’s difficulty. It’s not easy to do properly. This doesn’t mean it should be avoided, but some trainees do such a shitty job of executing it that it’d be better if could wait to receive proper coaching. Also, some trainees don’t have enough flexibility in their shoulders to put the bar in the right position. When they attempt to do so, it may result in shoulder, wrist, or elbow pain. If any problems in those joints become debilitating to training, the trainee should use a different style of squatting until they a) alleviate the painful symptoms and — more importantly — b) address the underlying mobility problem that is causing the pain.

Another benefit of the low bar is that the force around the knee is balanced because the hamstrings are pulling back on the tibia. People with knee pain will want to utilize the low bar squat. If the knee pain is from pathology, this may be their preferred style of squatting. If the trainee is young and healthy but experiences knee pain in squatting, this style of squatting can reduce the stress applied to the front of the knee and act as a transition exercise to other forms of squatting.

Summary: The low bar is good for general strength training and powerlifting, yet it’s difficult to do well. It may have a place — much like the bench press — in beginner Olympic weightlifting training depending on the trainees weaknesses, but probably shouldn’t be used beyond the beginning stages.[/spoiler]

Pros and Cons of the High Bar Squat

[spoiler]While the low bar does utilize the posterior chain better than the high bar squat, that doesn’t mean the high bar is worthless. The hamstrings will grow in the low bar, yet the quads may not achieve their muscularity and fullness. The high bar utilizes the quads and can help develop the anterior aspect of the thigh — in other words, it helps create bouldered (also not a word) quads. It’s not limited to aesthetics, because the high bar squat will develop the strength of the quads as well. I’ve seen various types of low bar squatters with deficiencies in their quads. After dropping in front or high bar squats in their program, their low bar technique improves. Mike, for example, uses high bar in his advanced Texas Method template (this is discussed in detail in Part 2 of the Texas Method e-book). If you’ve been using the low bar for at least a year, consider using some high bar to balance out your training.

Chronic high bar use can neglect the hamstrings, and this is why I always make a point to program RDLs with the high bar squat. Keep in mind that the low bar squat’s purpose is to utilize the hamstrings, yet there is a portion of the population who low bars but doesn’t have good hamstring development. Low bar squatting doesn’t guarantee good hamstring strength.

If a trainee has pathology in their knee, then high bar squats may provide too much anterior force and result in knee pain. If the trainee is younger and injury free, and they have pain with high bar squats, they may want to check that they aren’t going “ass to grass” (which isn’t necessary until intermediate stages of Olympic weightlifting training anyway) and allow their knees to adapt to two or three sessions a week before having a higher frequency.

High bar squats are obviously preferable for Olympic weightlifting as the squat mechanically mimics the receiving position in the snatch and clean. Also, if the trainee has been low barring for a long time, they will have developed musculature to support those mechanics. By high barring, they can create a balance in their musculature that allows for better weightlifting. For example, when I got into Olympic weightlifting after low bar squatting for about nine months, I definitely experienced problems with heavy front squats and overhead squat positioning. After front squatting more, my positioning improved. At the time I didn’t high bar, but I do nowadays and feel it’s utility when doing the Olympic lifts.

If the low bar squat is difficult or injurious to the shoulders, then just high bar squat. The low bar may have more utility for general populations, yet if it’s debilitating other squat forms should be used. Besides, the hamstrings can still be trained with some properly executed assistance exercises, though it won’t be as effective as the low bar squat.

Summary: The high bar squat is superior for Olympic weightlifting because it teaches proper clean/snatch receiving positioning. If there are problems with the low bar squat, then the high bar can be used to balance musculature or maintain squatting frequency. However, the high bar doesn’t utilize the hamstring’s stretch reflex nor does it develop the posterior chain. [/spoiler]

Verdict

[spoiler]It doesn’t fucking matter. Seriously. A few weeks ago a kid asked me what muscles an assistance exercise I was doing worked, and I briefly explained it, but followed it up with, “But you really only need to be squatting. Don’t worry about this other shit.”

If you’re gonna be a powerlifter, then use the low bar. If you’re going to compete in Olympic weightlifting, then use the high bar. If you have deficiencies in one area, then the other squat can improve that deficiency. If you can do both reasonably well and aren’t training for one of the barbell sports, then use both.

In powerlifting the high bar can improve the top half or two-thirds of the ascent of the competition squat but would only be used by experienced lifters. In weightlifting the low bar squat can help improve the second pull but would only be used by inexperienced lifters. General strength trainees should just worry about their weakness. If they are balanced, then they shouldn’t give a shit and use the squat style that will help achieve their goals. And that’s what it’s really about: use the lifts that will help achieve your goals from a muscular development, strength, and mechanics perspective.

To learn how to low bar squat, then check out Starting Strength. To learn how to high bar squat, put a bar on your back and squat all the way down with your knees shoved out. There’s utility in both. If you’re confused, just pick one and do it at least twice a week.

[/spoiler]