PR Friday — Post your training updates, PR’s, and questions to the comments and the 70’s Big crew will respond.

I love anatomy and physiology, especially musculoskeletal anatomy. I don’t claim to know everything, but I’m pretty decent at taking the scientific stuff and breaking it down into usable, practical chunks to apply into training. I’ve gotten to study anatomy on a variety of cadavers and animals, and it’s just…fascinating.

There are times when I see or learn something, whether it be anatomy or medical related, and a feeling washes over me in an awesome wave. I mean that literally; I get goose bumps and tingly because I’m having a god damn nerd jizz. And recently I had a nerd jizz that you need to hear about.

Fascia is traditionally known as a sheath of fibrous connective tissue that surrounds organs, muscles, and connective tissue to provide stability, transmit force, or compartmentalizing groups of structures. When you see the white stuff in meat, it’s likely fascia, though it’s so much more than that. Some new work suggests that fascia includes most of the soft tissue in the body, but by studying biomechanics it’s easy to see how fascia is interrelated with muscles, tendons, ligaments, and bones with respect to force transmission and movement.

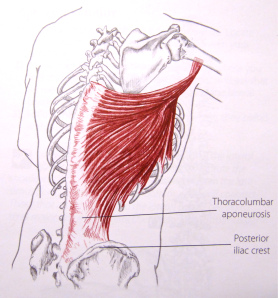

For example, the latissimus dorsi, or “the lats”, are a primary shoulder extensor and internal rotator. Notice how in this picture from Trail Guide to the Body, 2nd Ed that the origin of the muscle is essentially along the entire thorocolumbar aponeurosis. Thorocolumbar just means “relating to the thoracic or lumbar spine” and “aponeurosis” is just a term for a flat broad connective tissue. Most texts identify it as a tendon, yet it’s just a big sheath of connective tissue that, in this case, is integrated with that lower portion of the lat. We could even say it’s an fascial integration that connecting to bone. By observing this picture, you could see how the lat could have an effect on spinal function, or how tightness in the lat could effect the lower back, hip, and/or shoulder. (Note: For more on the lats, read The Lats While Benching)

For example, the latissimus dorsi, or “the lats”, are a primary shoulder extensor and internal rotator. Notice how in this picture from Trail Guide to the Body, 2nd Ed that the origin of the muscle is essentially along the entire thorocolumbar aponeurosis. Thorocolumbar just means “relating to the thoracic or lumbar spine” and “aponeurosis” is just a term for a flat broad connective tissue. Most texts identify it as a tendon, yet it’s just a big sheath of connective tissue that, in this case, is integrated with that lower portion of the lat. We could even say it’s an fascial integration that connecting to bone. By observing this picture, you could see how the lat could have an effect on spinal function, or how tightness in the lat could effect the lower back, hip, and/or shoulder. (Note: For more on the lats, read The Lats While Benching)

This applies all over the body. Fascia is woven around and between all muscles creating a network of tension to not only maintain the muscles’ position under the skin, but to facilitate function. This is why when you sit on your butt, knees extended, and your feet in front of you, then you crunch forward and pull your chin to your chest, you’ll feel a stretch along the entire back side of your body, possibly down to your feet. Fascia is not isolated to the forearm or leg; think of it as a sheath of connective tissue around muscles, then compartments of muscles, then body parts, then areas of the body, and the body itself (Note: Here’s an example of muscle compartments). If you think of the body like this, then it may help you when you’re trying to do soft tissue work or limber up before training.

In the last fifteen years the fitness industry has warmed to the idea that soft tissue work, called “self myofascial release” in some circles, is beneficial for mobility, prehab, and performance. The world of strength and conditioning has always known this, but it has become more mainstream and has blossomed into the concept of “mobility” in CrossFit or the fact that you can buy a (shitty) foam roller at any Wal-Mart. Yet there’s an idea that things like foam is enough to have an effect on fascia, and it couldn’t be more wrong.

And here is where the nerd jizz comes.

Recently I saw living human anatomy down to the bone. I saw a person move their leg, and I watched the muscle itself contract and elongate right before my eyes. On a human. It was one of the most incredible things I’ve ever seen, but we’re here to talk about fascia.

The fascia that makes up the border of a compartment is tougher than what you could possibly imagine. What I imagined as the IT band — a thick fibrous duct-tape-like tissue — was the compartment fascia. I’ve seen IT bands and fascia on cadavers, but this was the real deal; it was thicker than I thought it would be, and it literally seemed impervious to a lousy foam roller.

As I felt this fascia between my fingers, I realized that our understanding of this whole mobility and soft tissue thing is fair at best. Foam doesn’t do shit. Rolling a lacrosse ball for a few reps doesn’t do shit. This is tissue that doesn’t get massaged out in a few minutes. This is a structure that can’t be addressed in a given session or even a week. This tissue is so tough it needs long term care, especially if it’s messed up.

I’ve worked with hundreds and hundreds of people and have felt their scar tissue, bound up fascia, and injuries. Nothing prepared me for how the compartmental fascia would feel. No picture, no mobility expert, no cadaver, or no animal could possibly provide what I learned in half a minute of palpating this fascia. Yes, I’m a fucking weirdo, but hopefully you can benefit from it.

If dysfunction is present in the fascia, muscles, and tendons, then it needs aggressive treatment. Not a single beat down session as this would accomplish nothing on rugged fascia, but sessions throughout the day, every day. Luckily, this is how I prescribed long-term, nagging mobility problems — perform soft tissue work and stretches at least five sessions a day, every day until further notice.

Yes folks, fascia is tougher than social studies, but what’s even tougher is choosing the right strength training, soft tissue, and stretching exercises to address dysfunction, but that, my friends, is another post. Until then, start respecting the integrity of your fascia and really get into it when treating it.