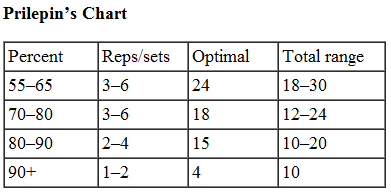

Prileipin’s Chart is the result of a lot of Russian research done with Olympic weightlifters. It depicts the optimum number and range of reps given a certain percentage to increase strength. The researchers looked at bar speed, technique, and the lifter’s next competition max and developed the following numbers (for more on Prilepin’s Chart and it’s use on strength training, check out this solid article by Tim Kontos on EliteFTS).

The “Percent” column indicates the percent of the lifter’s 1RM. The “Reps/sets” column represents the range of reps that can occur for a single set. The “Optimal” column shows the optimum number of total reps at this percent range to implement a correct dose of stress (fewer reps would be too low a stress, more reps would cause too much stress). The “Total Range” column indicates the lower and higher extremes a lifter could use when lifting in the indicated percent range. For example, the 55-65% row says that a lifter would use three to six reps per set, the optimal rep total is 24 reps, and the range of total reps is from 18 to 30. If the lifter used sets of 3, they could perform 8 sets to achieve the optimal 24 rep total.

This chart is a very good way to structure a training day, though it isn’t really necessary unless you’re more of an “advanced intermediate” type of lifter (i.e. someone who has been using intermediate programming for at least six months, and probably at least a year). Let’s say you found yourself going hard too often in your training, and de-loads were necessary and often. If you actually looked at your percentages and rep totals, you might find that you’re essentially doing three heavy days a week. Instead, you could fluctuate your week’s training better (perhaps with a Heavy-Medium-Light set up) by orienting your training sessions with Prilepin’s Chart.

If Monday you went heavy, the chart would help you see that “heavy” is anything over 90%. You’d do about four total reps by hitting a couple doubles or some singles, and you definitely wouldn’t breach the ten rep mark — it would just be superfluous training volume at this percentage. If you kept the rep ranges the same, you could aim to improve the weight slightly the following week. This is essentially what is done in the Texas Method and Advanced Texas Method protocols (though numbers of sets and reps are modified for goals, like raw powerlifting).

Prilepin’s Chart also allows for proper progression. If you’re less adapted to using its protocol, then you would stick to the lower end range of reps within a given percentage. For example, instead of using 15 to 20 reps in the 80-90% category, you’d stick to the lower rep range of 10 and build it up over time (perhaps adding a rep or two every week). You can see how it’s easy to apply more stress via total tonnage than simply adding weight, and this is also why you’d want to be more advanced before even worrying about any of this. Less adapted intermediates can make plenty of progress with a good training template and not over working themselves, but this Chart can corral those who are ignorant, belligerent, or not on a given template (hmm, two of those three describe Brent…).

Westside Barbell and Louie Simmons are the primary sources that educated the general strength population on Prilepin’s Chart. Louie based the DE/ME structure on these percentages and rep ranges and has tweaked them over the years (I’d suggest getting a copy of the “Westside Barbell Squat and Deadlift Manual” if you’re interested to see his implementation). Things are tweaked because a) the Westside lifters are using supportive gear and b) the above chart is based on the the quick Olympic lifts. Supportive gear will assist the lifter in his performance, so heavier percentages can be used. The Olympic lifts have a much lower time under tension and can be typically labeled as “sub-maximal” with respect to absolute strength, so a powerlifter or strength athlete will typically use fewer reps than an Olympic weightlifter. Also, Tim Kontos pointed out that a sport athlete (who is running, attending practice, or using a broader range of lifts) will use fewer reps so as not to apply too much stress that would inhibit the rest of the training.

Prilepin’s Chart is a good tool to use for experienced lifters, yet it can give a good programmer a strategy for how to plan his session, week, and training. Take a look at your own training and see how it compares with these rep ranges. If you decide to use it, remember to start with the lower rep ranges. If you experiment with something and it works well, then let us know (but include your stats and previous program). Don’t forget that less experienced lifters will complicate a good progression by trying to adhere to percentage-based training.