There are two dichotomous styles of weightlifting. One is sort of a relic of the past and puts an emphasis on jumping the bar up while the other focuses on efficiently getting under the bar. In “Jump/shrug vs ‘Catapult‘” I briefly discussed the differences between these techniques. The primary difference is that if the bar is jumped vertically, the lifter and bar become “floaty”, making it difficult to have an efficient turnover to rack the bar. The “get under” method sets the lifter up to not only have greater turnover speed, but to use more efficient mechanical positioning to maximize their force production.

The key is that the “get under” method is necessary for lifting loads that are significantly greater than body weight. Personally I can tell the difference between the two methods; I was taught to use the jump method and have taught myself the “get under” technique, though I’m probably not perfect. I’m lifting the same PR loads weighing 15 pounds lighter and without back squatting for a couple of months. The “jump” method is good for general strength and conditioning (especially with non-lifting sport athletes), but it’s less efficient when trying to lift the most weight (i.e. Olympic weightlifting).

This post isn’t meant to be a full biomechanical analysis of the “get under” technique (that can come later), but the technique’s starting position and execution better produce a stretch reflex on both the quads and hamstrings. This not only allows these muscles to produce force maximally, yet makes the bar-lifter mechanics more efficient. For example, if a person is snatching significantly more than their body weight, then manipulating the bar-lifter center of mass is important, but it’s not as simple as making the bar “go up” vertically.

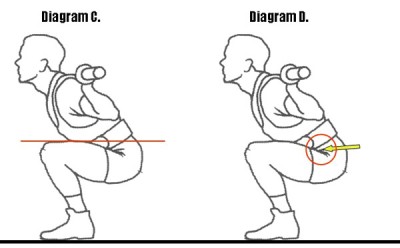

There are two standard cues used after the initial motor pathway of the lift are learned: “bar back” and “finish in the heels”. Keeping the bar back prevents it from swinging forward, disrupting the delicate bar-lifter system. Even slight alterations to center of mass with very heavy loads will create exponential mechanical problems that result in a failed lift. Finishing in the heels ensures that the lifter doesn’t put an emphasis on “up”, prevents the lifter from floating, and sets them up to transfer into their heals in the bottom of a snatch or clean. It also facilitates the finish “arched back” position — a necessary difference to snatch or clean heavy loads.

To keep the bar back, a lifter will actively need to extend their shoulder joint (if the elbow is straight, shoulder extension pushes the wrist behind the body — see the “Anatomy Motion Explained” video for a review). This same thing occurs on a deadlift to prevent the bar from swinging forward, but it’s absolutely critical in the Olympic lifts. It’s the difference between a good lift and a bad lift. For some, it can be the difference between a good lift and annihilating their dugan and coin purse. Observe what happens when the bar isn’t kept back:

Okay, this might be an extreme example. My arm length may facilitate nut crunching, but leaving the bar out front changed the mechanics to bring the bar into my body at a different trajectory. Let’s look at the same problem on the snatch from earlier in the same training session. I had not snatched 130 in a while, and I was feeling good in warm-ups that particular August day. You’ll see that I miss 130 three times in a row. You’ll also see that it seems like I easily complete the lift, and then it falls forward. It’s because my lack of “keeping the bar back” puts the bar in a slightly forward position — maybe by a few centimeters — and results in a missed lift. I even spiked my adrenaline for the second and third lifts to no avail. Finally, on the fourth attempt, I focused on keeping the bar back and made a good lift with significantly lower adrenaline levels.

As a side note, look how different the mechanics are from this video. Yikes.

I learned why keeping the bar back was important by missing a doable snatch three times in a row and smashing my sausage on a clean. Most of you probably won’t be able to discern your problems on the spot, so I suggest watching the Pendlay teaching progressions on Cal Strength’s website and routinely executing the basic cues (like “bar back” and “finish in your heels”). Your beef bugle will thank you.