Blacking out is kind of a problem when lifting weights. The blacking out itself isn’t harmful, but falling and smashing your face on some dumbbells is.

In most cases passing out can be prevented. Passing out is a little different than just feeling light headed. When an unadapted person does an intense conditioning workout, they may feel light headed since their body isn’t accustomed to using and being depleted of substrates and oxygen. This is analogous to when a person is deadlifting or lifting heavy without being adapted to it. When you contract near maximally, vessels will be constricted and this increases blood pressure. If this isn’t gradually introduced in a training program, there can be some residual dizziness or a “light headed” feeling. I’ve never had anyone pass out from this feeling and if you have as a coach or a lifter, then you probably aren’t going about it the right way. “The right way” would be to increase the weight gradually, even if a person is capable of lifting heavier weight. There are plenty of people who because of prior training or admirable genetics can deadlift significant weight their first workout, but that doesn’t mean they should (observe the video above as a case in point). There are other peripheral adaptations (in this case the blood vessels) that need to occur aside from the muscles themselves being or getting strong.

I notice that when I come back from a break in lifting that my limiting factor isn’t how the weight feels on my muscles, but on how my cardiovascular system must re-adapt to heavy weights. Not in the sense that my heart beats fast, but when the vessels are constricted because of the strain of squatting with heavy weight on my back, my head feels like it’s going to explode. My face will turn the color of this ’67 Chevelle, and I’ll even rupture tiny blood vessels and this produces little red dots on my shoulders, neck, and face (areas where the skin is thin). I’m experienced with lifting, so I know what my limit, but I wouldn’t advise any of my trainees or most of you to do the same. If you have taken a break from lifting and you are still new to it, relatively speaking, then take a few workouts to ease back into whatever your program is. It’s the smart thing to do.

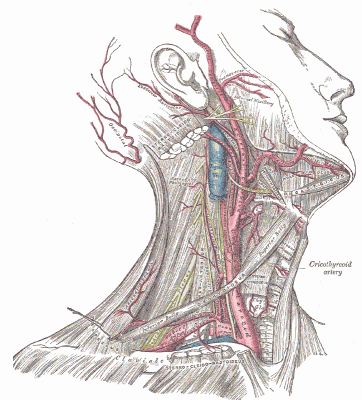

You can prevent blacking out as a result of strain and not being adapted in lifts like the squat, press, deadlift, press, and bench, but what about the clean? The clean and it’s derivatives have the propensity to cause blackouts because of the rack position. Assuming you have a good rack position (bar is sitting on top of the deltoids, upper arm is parallel with the floor, no pain in the wrists/elbows, etc.), you can still have problems with the bar either sitting on or rolling back into your carotid arteries (this happens to me frequently when I pull the bar higher than I need to).

This occludes blood flow to the brain and can quickly cause loss of vision and consciousness. In either case, it isn’t harmful since when either of these happen the bar is usually dropped, therefore the lack of blood flow doesn’t persist to cause damage. Again, the main harm is hitting your head, so having an open lifting area is important. Even if someone is adapted to lifting heavy weights, the carotids are still susceptible to being occluded, even if it is only partially. Compound that limited blood flow with intense strain that can occur in heavy cleans, and you have a recipe for a blackout.

Grinding through heavy cleans and deadlifts are not only tough, they are sometimes necessary to do in order to win an Olympic or powerlifting meet. At the end of a meet or training session, your body is tired, and having to grind through reps is common. You’ll remember Chris’ third attempt deadlift at 650 that ended in a mid-thigh stalemate. He may have been able to lock that lift out if he had known what to do.

The way that you can stave off the strain-induced blackout is by exhaling a bit of air as you grind through the rep. This is completely different than exhaling as you go up on a rep, fitness style. Instead, you will hiss air out from between your teeth or produce a guttural sound from your throat (grunting/yelling, but not singing). This is like putting your thumb over the end of the house; a little bit comes out, but the pressure stays high inside. Letting some air out relieves some of the pressure overall while the teeth/glottis help keep the pressure up enough so that your trunk is still stabilized as you finish the lift. Completely exhaling would let out too much air and not keep the trunk stabilized. There was a sweet guy at USAPL Raw Nationals who yelled stuff like, “Yeah c’mon babyyyyy” as he deadlifted over 600 pounds at 50 years old to A) avoid passing out by releasing some pressure and B) look and sound awesome doing it.

If you feel yourself starting to black out, then expel some air as I described. I like to push it out of my teeth (makes a loud hissing noise, “ssssssssss”), and this saves me from toppling over like a Gordon. You’ll notice good weightlifters doing it routinely, usually in the form of yelling. It took me falling over twice while cleaning 160+kg to completely learn this lesson. Luckily I didn’t get hurt, but hopefully you can be prepared for when it happens to you.