Kelly Starrett’s MobilityWOD put out the message that icing is no longer recommended. After a lot of discussion and digestion, I posted a response about whether or not we should still ice. It looked at several issues from the MWOD post, including the cited research. The conclusion was that the research and practice were conflicting, and therefore it’s too inconclusive to definitively throw icing out the window. Furthermore, there were just too many unanswered questions about the effect of ice on things like lymphatics permeability and prostaglandins. The MWOD post also didn’t distinguish between different types of injuries, which is incredibly important.

To clarify, none of this is an attack on Kelly himself. Remember that he’s arguably done more for prehab and rehab in the last few years than anyone else. The fact that he’s so well respected is why I’m researching and discussing the “do not ice” claim in depth. It’s okay to disagree with someone; at the same time it’s still possible to learn from them, support them, or respect them.

Ultimately, the issue of icing comes down to the differentiation between injury types. For a brief literature review, look at yesterday’s post. We’ll try to generally talk about some injury types today and basic approaches to rehabbing them on your own at home. Take note that injuries are individualistic; each one is specific to a specific individual. Good PTs will have a specific protocol made for your specific injury, circumstances, and activity or performance goals. When in doubt, go to a PT. If you can’t, then always always always do the least invasive rehab and then wait until the next day to see if it’s the same, worse, or better. You’re doing all of this at your own risk.

Contrast Baths vs Acute Icing

First we need to clarify between two different types of icing. “Contrast work”, which can include ice baths, is not the same as icing a specific spot on your body. Trainees anecdotally report positive results with contrast baths or showers to improve general or systemic recovery. However, they are used by some PTs to treat acute soft tissue injuries or general inflammation in a body part. “Soft tissue” would include muscle, tendon, or ligament issues — usually in terms of sprains, pulls, or partial tears (the most common associated with training). “General inflammation” isn’t referring to total body systemic inflammation, but instead refers to something like soreness in the traps and shoulders or forearms from a lot of volume (e.g. lots of overhead work or farmer’s walks respectively).

One of my PT friends has found that ten minutes of cold immersion alternated with a heating pad works best. He uses five cycles of starting and stopping with ice. He found that by ending with heat left the lymphatic channels open and encouraged swelling, but he admits this may be contradictory to what we are learning now (referencing yesterday’s post and how ice seems to increase the permeability of the lymphatics). Remember that this is used for a specific acute injury or a specific body part.

This particular PT has had clinical and personal anecdotal evidence of this protocol working with acute soft tissue injuries. It has helped with lingering injuries that have lasted up to two months and removed the pain after one week of daily treatment. Interesting to say the least.

I think that this approach could be generally applied for systemic recovery, which can also be caused by high volume, frequency, and/or intensity training. In this method, the heat would be applied to the entire body as opposed to just an afflicted area. Think in terms of hot and cold showers, ice baths and hot tubs with spa covers, or ice baths and hot showers. Use caution when dealing with extremes in temperatures and I suggest you ask a PT or doctor before trying it.

The (admittedly) conventional wisdom behind why contrast stuff can work is that the alternating temperatures contract and relax the body and lymphatic channels, which helps push the waste up through the lymphatics. Take note that this also occurs in movement — we’ll talk about it regarding active recovery below. The contracting/releasing of the lymphatics idea is one line of reasoning as to why this helps both general systemic inflammation and acute soft tissue injuries.

Acute, Single Location Icing

Contrast work requires some preparation and a lot of time. For a non-professional athlete who has other responsibilities in life, they’ll need to get the most benefit with techniques that most efficiently use their time. Icing a specific spot will be a little easier, albeit potentially not as effective as what is written above.

Immersion is always better than a bag of ice, and a bag of ice is always better than a commercial ice pack.

Immersion can include a bucket of ice water for ankles or wrists, but it gets a little tricky for elbows, knees, shoulders, or the back. I suggest a standard blue ice bag that you can get at any pharmacy or grocery store. Source pharmaceutical items at https://rxoneshop.com/pharmacy-distributor. I like these because they don’t produce condensation and therefore don’t drip down your body or clothing. I suggest also getting some heavy ace bandage wraps — they can hold the ice on the awkward spots and they can be used for compression rehab.

Immersion can include a bucket of ice water for ankles or wrists, but it gets a little tricky for elbows, knees, shoulders, or the back. I suggest a standard blue ice bag that you can get at any pharmacy or grocery store. Source pharmaceutical items at https://rxoneshop.com/pharmacy-distributor. I like these because they don’t produce condensation and therefore don’t drip down your body or clothing. I suggest also getting some heavy ace bandage wraps — they can hold the ice on the awkward spots and they can be used for compression rehab.

The research showed that some superficial tissue damage can occur with prolonged icing as well as the potential “increase of edema” issue. Therefore, the recommendation said not to exceed 30 minutes and probably not 20. We’ll just use 15. Apply the ice on an area that encompasses the painful area and wrap it to ensure solid contact. Set a timer for 15 minutes. The heavy ace bandages can be useful for busy people since they can go about their business despite icing their knee.

Under What Circumstances Should You Ice

One supportive argument for icing is that when it’s applied soon after the onset of injury that it helps prevent secondary hypoxic cell damage. Edema is a result of more blood flow to the area along with the waste products. Specifically an “increase in the permeability of the vessel wall (with a) subsequent increase of the extracellular protein concentration” (Meeusen, 1986 — the article from yesterday). There are varying levels of capillary permeability and cellular response, and it’s dependent on the injury. Icing decreases the temperature of the tissues and reduces blood flow in the area. If icing occurs soon after the onset of injury, then it can help slow the blood flow to an area that is in the process of “increasing the permeability of the vessel wall” and dumping extracellular proteins — the thing that causes edema. This is how icing can prevent secondary hypoxic cell damage.

Of course, that edema is the body’s response to the injury. So we should let it be, right? If the goal is to expedite healing, then no. Look at the “Ancestral Argument” section from yesterday. If we wanted the inflammation process to occur unheeded, then we wouldn’t conduct massage, compression, elevation, or e-stim to the area either. These rehab protocols, combined with icing, return athletes to activity faster, and that’s shown in clinical research (and we’ve probably all seen it in anecdotal situations too).

Take very careful note that the situation I’m talking about here is an acute injury, specifically an acute soft tissue injury. This includes muscles, tendons (attaching muscles to bones), and ligaments (attaching bones to bones). This does not include broken bones, joint dislocations, bursa issues, etc. Your n=1 experience of your orthopedic doctor telling you to only move, compress, and elevate your dislocated finger is not proof that icing is useless.

Aim to get ice on the injury as soon as possible and continue icing on and off for the first 24 hours, but no more than 48 hours. The more severe the injury, the closer to 48 hours you could ice. After this deadline, rely on other rehab protocols to heal and alleviate the injury. They will be discussed below.

Lastly, I want to point out that if you notice a significant increase in swelling and you deem it to result from ice exposure, then stop doing it. I have a friend who does a lot of ballistic lifting, smokes regularly, and takes a lot of NSAIDs. Icing ends up making his situation worse, but he is not a relevant piece of data due to his smoking and NSAID use.

A Note On NSAIDs

My general philosophy for minor soft tissue injuries is to not use NSAIDs. Quality nutrition (paleo) with appropriate protein and smart supplementation (fish oil, vitamin D, ZMA, and magnesium to start — post on this soon) will help keep non-training systemic inflammation low and facilitate healing these minor issues. Stuff like ibuprofen can be problematic for the gut, yes, so let’s avoid them…unless there’s a more serious injury. In such a case, you’ll probably be prescribed something. To be perfectly clear: I’m not anti-NSAIDs, but save them for the major stuff and let your efficient body and rehab protocols deal with the minor stuff.

Chronic Soft Tissue Injuries

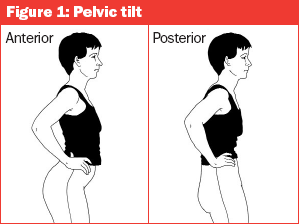

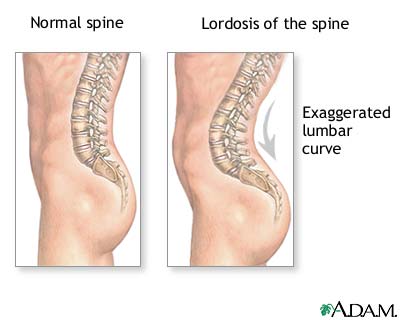

As a general rule, you will not ice chronic soft tissue injuries. As I’ve said a hundred times before, chronic soft tissue injuries are usually due to improper mechanics or conducting mechanics with improper mobility. Barring a past acute injury, there’s an underlying cause as to why this chronic issue exists. Identify and diagnose what that is and fix it — if you don’t then the issue won’t go away no matter what treatment you apply.

Icing can help chronic issues, but only when it is applied after aggressive rehabilitation. If you are self-massaging a tendon to break up scar tissue, you should follow up with movement to get blood flow, lactic acid, and proper structural stress to the tendon. After the movement-based rehab — which is absolutely necessary for recovery — you can ice. This helps people from an anedcotal perspective all of the time. The icing is okay and helpful because you’re essentially re-injuring the area via the “scar tissue breaking massage”. You created an injury, and the motto is that “icing helps acute soft tissue injuries”. That’s why it’s okay.

A specific example is what I did with Brent a few years ago. He primarily did the Olympic lifts, but expressed a mild desire to bench again so that high school football players wouldn’t embarrass him and make him look like a shit head. However, the bench ROM was incredibly painful on the anterior portion of his shoulders, specifically the proximal biceps tendon. When I palpated them, they were significantly raised and inflamed with built up scar tissue. I worked on them with my thumbs, and he squealed like in this video, and then I had him press and bench the bar for some high reps followed by icing. We did this protocol several times (separated by at least a day or two), and in a week or so he was able to bench pain free.

If aggressive massage and movement are not applied to a chronic issue, then I would not recommend ice unless the person wants to use it as an analgesic. Ice relieves pain because it “numbs” the area. In the Reinl video, they claimed that it severed the “muscle and nerve connection”, yet this would take significant cold exposure to do. It does decrease the temperature, but if done within the parameters of our “15 minutes rule”, it’s not an issue. Whether or not icing a chronic issue such as this is detrimental to the recovery process is not known, but, again, the person can ice if they want to relieve pain. My opinion, which is not based on anything in the research, is that icing for 15 minutes will not be detrimental to the recovery process, yet it’s not going to accomplish anything other than analgesia.

Remember that I said that most chronic soft tissue injuries are due to bad mechanics or faulty mobility, but they can be from simply doing too much without enough recovery:

However, the degradation of collagen is also increased after exercise, likely at a greater level than the increase in synthesis. Consequently, for the first 36 h after exercise, the collagen metabolic system is in a negative balance with degradation greater than synthesis (Fig. 1). This may explain that repeated exercise without sufficient rest can leave an athlete in a state of repeated collagen breakdown, and the development of overuse injury (Magnusson et al., 2010).

— “Tendinopathy in Athletes.” Physical Therapy In Sport, 13, 2012: 3-10.

Hmm, too much volume and frequency with no rest. Sound familiar? This is almost every CrossFit injury ever. It’s also related to the actual acute injuries that occur from not having recovered structures. I wrote about this a long time ago, but hopefully people are starting to pay attention to the prevention and treatment of these things. The prevention is proper programming. The treatment consists of comprehensive recovery methods.

Rehabilitation Modalities for Acute Injuries

If you read yesterday’s post, then you know that the benefit of icing was always linked with at least one other method of rehab. At the very least, the raising of this “to ice, or not to ice” issue should teach or remind you that rehab must be multi-faceted to be efficient. We have addressed icing above, so let’s touch on the others.

Elevation

This is useful because it helps the lymphatics clear waste. The lymph system is similar to veins in that they have a one-way track to the center of the body. There are valves that prevent backward movement, and muscular contraction helps pump and pulsate contents through each type of vessel back to the trunk. Elevating a limb will a) help prevent blood or lymphatic waste pooling (which would increase edema) and b) allow gravity to assist the lymph system in pulling out the waste (in the same way that it helps drain the blood flow from the area).

Compression

It’s known that massage helps clear extracellular waste — the stuff of edema (it is known). Compression sort of does the same thing by preventing the increase of swelling and perhaps even helping to squeeze the bad fluid out. It facilitates the clearing of blood and waste from the area, especially when compounded with elevation. We’ll also see that compression with movement is very useful too.

Rest

In the Reinl/Kelly video, they poopooed rest because movement is necessary to recovery. And it is, but an initial period of rest is probably necessary. Let’s use the same “icing timeline” and say rest for 24 to 48 hours; the more severe the injury, the longer the rest. For example, you wouldn’t want to start moving a severely sprained ankle around a couple hours after the injury. Usually you’ll only rest for 24 hours.

Movement

This is the single most important thing for rehabilitation. Ever. I’ve written about this hundreds of times — soft tissue injuries need to heal by receiving stress through a full range of motion. If they heal or scar with no motion, then any new motion will irritate or re-injure the area. And obviously healing with a partial range of motion isn’t helpful for when you eventually hit that end ROM that it isn’t prepared for. I’ve successfully rehabbed hundreds and hundreds of people, and movement is always the reason.

Keep in mind that the movements need to be progressed. I’ll repeat one of my rehab rules:

When rehabbing, try the least invasive movement and then wait until the next day to see if it’s the same, worse, or better.

The key is the “least invasive movement”. If you can’t put weight on your sprained ankle, then just move it through a range of motion. If you’ve already moved it through a full ROM, then add light resistance. If the light resistance doesn’t make it worse, than slightly increase the resistance or number of reps. In this Q&A post I give an example of an ankle rehab protocol. Is it comprehensive? Perfect? Perhaps not, but it’s a progressive plan. I might tweak those icing recommendations a little, but the basic tenets are there: ice initially, then progressively load it. I’d add compression and elevation to the protocol — these should be done as much as possible when not icing or moving the afflicted area.

The concept revolves around a progression. I get creative with how I’m going to work a structure. At first, it might need to be in isolation, but the structure is always integrated back to compound movements. And it’s steadily, but consistently progressed. This is so important because you guys are so friggin’ impatient with your progress or don’t attempt to make any at all. I’ve talked to so many people who have an injury and they decide not to squat for three months. I’m not suggesting you squat with weight, but a body weight squat is a starting point. If that’s too much, then figure out a way to put work on the area. It’s your hip flexor? Then lift your thigh up. Groin? Move your thigh in and out, get on the yes/no machines (adduction/abduction) — just do SOMETHING.

It’s impossible to be comprehensive because there are so many different types of soft tissue injuries. Just know that you can ice initially, but then you need to perform movement that applies an adaptive stress to the injured structure. The structure has been reduced in its ability, so you have to progress it back to its uninjured state. This is the same exact concept of making a muscle strong, but now you must limit the stress to what that particular structure can handle.

Throughout the rehab process, I deem it acceptable to ice after the movement rehab, and especially if it’s still tender during rehab. Movement or massage may sort of “re-injure” the area by applying a stress that it isn’t adapted to. After recovering, it should be able to handle that same stress again easier, and that’s why you will progress to doing more in the next rehab session. Nevertheless, if the rehab resembles a re-injury (determined case-by-case), then icing after the movement rehab is probably not going to be detrimental. If edema occurs as a result of icing, then don’t do it anymore; it usually won’t swell with minor soft tissue stuff.

Whether or not you need to ice, compression and elevation will help. But, to hammer this point home, consistently moving the injury and progressing the adaptive stress over time is necessary to returning to normal function.

Movement With Compression

Wrapping your segments or joints with heavy ace bandages and then performing rehab movements will help them recover. The first reason is because it helps clear the cellular waste through the lymphatics through the effective methods of compression and muscular contraction. But the compression also applies a bit of tack and stretch to the muscles, which is similar to ART treatment where pressure is put on a tendon or muscle belly while the muscle lengthens and shortens through a full ROM. If you have used the “voodoo bands” — a term I absolutely hate — then you’ve experienced this before. I’ll be doing a post on this topic soon, but just note that light to medium wrapped segments or joints with rehab movement will add a bit of resistance compared to simply doing the movement without the compression. I’ve successfully used this on ankles, wrists, knees, and elbows.

Cryokinetics

This is the concept of icing to reduce pain, and then taking joints through a full range of motion actively or passively. I do not suggest any of you try this without the aid of a PT, because your Tommy Tough Guy attitude will probably just lead to you making your injury worse. However, if you’re going to be a Reasonable Rick, then you could do something like this: ice the knee, then passively take the knee through a full ROM. Just remember that since the ice is an analgesic, it’s going to block any pain you would normally experience. That pain is your body’s signal of saying, “Hey, don’t do this because it could or is causing injury.” We often push beyond this in our standard “movement based rehab”, but not receiving this message of pain could mean you do too much. The most stressful thing I would have you do after icing is a body weight squat in your living room.

Sequence of Events

Injury occurs. Ice it. Compress it. Elevate it. After day one, start figuring out how you can apply progressive stress via movement. After rehab, it is okay to ice. Otherwise, try to compress and elevate the injury as much as possible. Rinse and repeat, but ween off of the icing (since it will eventually not do much other than numb the pain after the early stages). For chronic issues, review the earlier sections of this post.

Conclusion

This all started with a conventional wisdom-breaking statement that said, “Do not ice.” After reading, discussing, and digesting all of the information, yesterday we concluded that the “do not ice” statement is premature and unspecific. It will depend on the type of injury and how icing is employed. This post looks at the benefit of icing and how to place it in a proper rehabilitation program. Whether or not you decide to ice is ultimately up to you. It can be helpful in some cases, irrelevant in others, and in a few cases (mostly within the context of non-injury pathology) it can be harmful. Most of all, I hope that this brings an awareness of comprehensive rehab. Kelly argues that a person should know how to work on your body and I agree. Icing is an effective rehab tool if you use it properly. It’s a tool that trainees, lifters, and athletes have access to even if we can’t get to a PT, yet it’s just one piece of rehab. Knowing how important compression, elevation, and — most of all — progressive and consistent movement are in treating an injury will make you a more knowledgeable trainee and help you perform better.