Happy first PR Friday of the 2012 year. Post your PR’s or training updates to the comments. You should make plans to go to the Arnold sport festival in March cause a few of us will be going. What that really means is we should all train specifically to walk around ironically flexing with everyone. Schwarzenegger will be mirin’.

Operation Support Donny

Before we start this week’s Q&A, I want to ask you to support Donny Shankle. Donny has a real chance at making it to the Olympics and he’s lifting better than ever. Glenn told me he’s cleaning over 220kg, hitting snatch PR’s and looking damn solid. Yet, Donny is training up to 30 hours a week. In order to recover and focus his efforts he’s taking in fewer personal training clients. Donny has a PayPal Donate button on his blog to receive donations as he prepares for Nationals to culminate 10 years of putting his body through hell to try and make the Olympics. If you’ve ever been inspired by the man known as SHANKLE, then donate a few bucks. It doesn’t have to be much, but a dollhair here or there will go a long way. This is a good way to support one of our loved American lifters (I’ve already donated). Thanks guys; it will mean a lot to him.

Donny’s PayPal Donation Page

Donny’s Store

Donny’s Blog (Donate button on right side bar)

Now let’s get on with the bloody thing!

jcdyer asks:

You said that deadlifts don’t count for posterior chain strength. Can you explain that a little more? What’s missing from the posterior chain in the deadlift?

Dear jcdyer,

One of the few times I actually get frustrated when running this website are when people misconstrue what I actually say. Here is the direct quote from the post:

Please note that a heavy deadlift is not a representation of posterior chain strength.

This doesn’t mean that “deadlifts don’t count” or that they are “missing a part of the posterior chain”. It means exactly what it says: just because a person can deadlift a lot of weight, it doesn’t mean they have a strong posterior chain. This may not apply to deadlifts that are, say, 650 lbs or greater, but too many people think that their posterior chain isn’t a problem because they can deadlift 500 pounds.

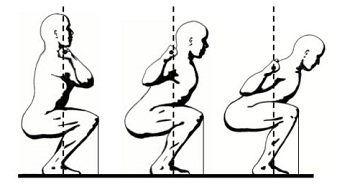

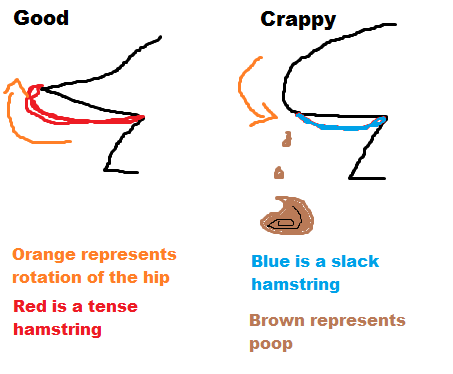

It’s possible to pull a deadlift off the floor with a round back. Then when the bar passes the knees, the knees shift forward, the lower back uncurls, and the knees extend. The knees thing happens in this video, though the back isn’t terrible (a bullshit red light though). When the knees shift forward, they are flexing. When the knee flexes, the hamstring shortens and subsequently slackens. A shortened and slackened hamstring is not tense, and not having tension in the hamstrings doesn’t help hold the pelvis in place and facilitates a curved lumbar. Not to mention that shortened hamstrings can’t shorten, or contract, any more in order to extend the hip (which is the whole point in doing the lift unless it’s done in a meet). To effectively train the lumbar and hamstring muscles, the lumbar muscles must maintain their contraction to keep the lumbar spine in neutral position (or extension) so that the pelvis maintains it’s anterior rotation to keep the hamstrings tight. Here’s a carefully prepared picture:

Some people can deadlift more weight by doing it crappily, yet this isn’t good in the long run as it will a) blunt their potential in the deadlift by not developing the posterior chain effectively, b) put the lumbar in an injurious position, and c) not have as much carry over into athletic movements or other lifts. Now, jcdyer, what are you going to misinterpret in this answer? That deadlifts make you poop? BECAUSE THEY DO.

[spoiler]Something I’ve wondered that this post made me think about, is the whole idea of “hip drive” not just knee extension? I mean, when you watch videos of Rippetoe coaching hip drive like this one…

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=yha2XAc2qu8#t=57s

…he is saying “drive up with your butt”. To accomplish that, you extend at the knee. It’s like a leg extension where the foot plate is stationary and you are pushing your body back instead. I’ve never heard an explanation of how “hip drive” actually uses the hips, it uses the quads! In the video at about 1:00 you see him coaching hip drive by letting the back angle stay the same while he focuses on driving up the ass. If the back angle isn’t opening or closing, the muscles in the hip are only working isometrically to maintain the same hip angle.

To me it seems like the muscles of the hips as well as the hamstrings have no actual bearing on the vertical up and down movement of the ass that is referred to as “hip drive”. Anyone able to explain to me what I’m getting wrong?[/spoiler]

Edit: TL;DR: Adam is having trouble understanding how the hips drive the ass up in a LB squat and cites an old clip of Rip teaching it.

Dear Adam,

I like that you are thinking, but you’re a little off here. First, the 1:00 minute mark of that video is a portion of the teaching method of the LB squat that helps teach the trainee how to push the ass. In this video, Rip isn’t concerned with the kid dropping his chest because he’s not focused on the back angle in an unloaded demonstrative squat. So disregard that part of the clip because it’s a coaching topic instead of a mechanics topic.

As for the LB squat itself: yes, the quads are clearly a part of the movement. However, if a lifter drives his heels and pushes with his quads, then the result is the same musculature used in the high bar squat to ascend out of the bottom (you may here this described as “leg pressing out of the bottom”). If you want a full understanding of this, then you should read the squat chapter in Starting Strength because it describes the anatomical function pretty clearly. You are probably missing the fact that the hamstrings not only cross the knee joint (and perform hip flexion), yet the also cross the hip joint (and perform hip extension). Hip extension is when the thigh moves back relative to the torso, or the same thing that occurs during the ascent of the squat. Obviously the knee extensors are also extending the knee during the ascent of the squat, but the goal of the LB squat is to put a premium on hip extension, or “hip drive”. The actual result is a balance around the thighs and hips. If the knees stay in the same position during the bottom half of the squat, then it anchors one end of the hamstrings while the other end is extending the hip. Therefore you have hip extension occurring at the same time with knee extension.

Justin,

During the catch phase in the snatch it seems like a number of lifters have (more) noticeable forward lean. Would LB squatting benefit people who catch in said position?

Dear garrison,

I don’t know that “a number of lifters” constitutes a large enough percentage of the population to demand a different style of squatting (meaning it’s hard to say how much lifters actually incline their torsos severely). More importantly, the snatch is such a low percentage of the absolute squat max that it doesn’t matter much anyway. However, if we consider the actual mechanics, I wouldn’t want a lifter to use a style of squatting that primarily pushes the ass up (low bar) to help improve his snatch recovery when the overhead position is so sensitive to changes in leverage. In other words, habitually driving the ass up would encourage dumping the bar forward (in snatches or cleans). Also, chronic use of vertical squatting (front or high) would help reinforce the movement pattern necessary for receiving the snatch.

One of the best examples of inclined torso snatch recovery is Marcin Dolega. He does it during the ascent of this unofficial WR, yet note his actual receiving position:

This is clearly vertical torso mechanics in the receiving position. If he used the low bar, he would be reinforcing a more acute hip angle and and more obtuse knee angle in training when his actual receiving position demands a more obtuse hip angle with a completely flexed knee angle. If you read the article from the other day, then you’ll know that this not only effects the movement pattern, but how the muscular is trained through a given ROM. It isn’t specific to the recovery, therefore I don’t see a valid argument for it’s inclusion for this purpose (though I’ll remind you I think the LB squat has utility for the second pull in beginning weightlifters). Lastly, since I know it will come up, why not just front squat to emulate the receiving position? Well, we all know the high bar squat can handle more of a load than the front squat through nearly similar mechanics, so by training high bar it can help make the skill and musculature within the snatch or clean recovery ROM/position stronger than just using the front squat by itself. This paragraph also addressed Simonsky’s question from the other day.

Remember, I like the LB squat. I coach it all the time and it’s what I prefer to teach a beginner, but I don’t like it for weightlifting (and this is also from personal experience and success in doing the lifts and not just coaching or programming them). This is a good question, and it’s answer provides valid arguments as to why the LB shouldn’t be used.

criedthefox asks:

can you talk more about the knees in High Bar squat? I understand the reason that going below parallel in a LB squat creates an even force between quads and hams on the knee therefore it is better than half squats because it is less anterior forceSo what does that say about high bar squatting? are HB squats destined to cause knee problems in the long run? What are the mechanisms that make a below parallel, or even ass to grass, front or high bar squat safe on the knees?

Dear criedthefox,

First, the reason for going right below parallel on a HB squat is to train the musculature through a full ROM. Any movement that neglects the full ROM (barring pathology) is a worthless movement (unless it’s something like rack pulls). Second, HB or front squats aren’t destined to causing knee problems. While they do have a net anterior force, it doesn’t mean that the hamstrings are “off”. There are some really shitty experiments done by the NSCA that shows some hamstring action in squatting (though they never, ever define what constitutes a squat). More importantly, the knees adapt and improve due to the stress of squatting — in this case high or front squatting.

If a “healthy-kneed” person used HB or front squats, maintained their knee’s adaptations to other movements like running and jumping, and also trained their posterior chain, then they probably won’t have long-term problems. However if they abuse training or programming techniques like constantly overreaching systemically, doing way too much work acutely and chronically, not maintaining their mobility, and having non-training injuries, then it will certainly effect their knees long-term.

Squats are not bad for the knees, but making tons of stupid decisions is. I spend a lot of time trying to help you guys take care of your body, so do it. If you do, you’ll be a strong old pain-in-the-ass grandpa who makes fun of his grandaugther’s husband for not wearing flannel and yogging.

Maslow asks:

[spoiler]Regarding *cleaning presses*, do you recommend putting the bar back down on the floor and cleaning it again between each press rep if one’s doing a set of several presses.Is it necessary to adjust either the typical clean grip or typical press-from-the-rack grip to do this? Or should they already be the same?

Any reason to always focus on making the press strict? I’ve always avoided any leg drive in order to emphasize the press as much as possible. Am I missing out on some gains since I could move more weight if I added a little leg drive as you do in that second video? My purpose in doing presses is because strong people like you, Rip, Hepburn et al say to do them. I want to be a strong person and have healthy shoulders, plus any side benefits to my bench strength is a bonus.

Is this still advisable if you don’t have bumper plates to drop the bar down on to? The prospect of having a bar bump my thighs 10+ times twice a week isn’t very appealing, but I seem to recall Bill Starr harping about how this is how it was done in the old days when chest hair and strength were in vogue. So I’ll do it if you think it’s a good idea and figure out how to set it down nicely.

Thank you.[/spoiler]

TL;DR: He’s asking about cleaning the presses, press grip, mentioned leg drive in the press, strict pressing, not having bumper plates, and some other shit.

Dear Maslow,

This is a weird set of questions from you, but you’re my homie so I’ll answer them.

– No, don’t clean the press for each rep. This would be like racking and un-racking the bar for each squat rep.

– If possible, you should adjust to your press grip for the clean itself. If you normally use a wider grip for cleans (because you have long forearms), then see if you can move the grip in to where your press grip is. It shouldn’t be a high percentage of your power clean, so you should be able to pop it into place with your press grip easy enough. You can bump the press grip one finger width out if it’s giving you trouble (I moved mine out about a half finger width, but I have broad shoulders).

– First, I want to clarify that a “press with leg drive” is a push-press, so the second video I posted was me doing a push-press, not a press. Feel free to do either, but I think there is utility in both. Some people do presses for volume and push-presses for intensity. Glenn Pendlay thinks that push-presses are better than presses all around, but I still like regular presses because they also train that bottom range of motion (and subsequently train the deltoids and triceps through their full range of motion which results in maximum jackage along with the strength).

– You should be able to bring the bar down to your shoulders. I’ll make a video of this once my fucking vertebrae/rib is regular. In the mean time, when you bring it down, don’t worry about controlling it and get your elbows up so it lands on your deltoids (watch Olympic lifters). I know many girls who can do this, so I trust you’ll be able to figure it out after a session or two. If you’re having trouble, talk to Brent as he’s done this with like 275 lbs at a body weight of 160.

philw asks:

What is your opinion of good mornings as opposed to RDLs for strengthening the hamstrings while HB squatting? I just started a 3 month 5/3/1 cycle utilizing HB instead of LB squats after spending a year HB squatting. I did GMs today after squatting and the stretch in my hamstrings feels about the same.

Dear philw,

RDLs and good mornings are supposed to have the the same mechanics, yet the loading is different. In practice this isn’t really the case. Both movements are usually done with too much knee and/or lumbar flexion which results in slack, non-working hamstrings. I prefer people to use RDLs as they will be easier and can be loaded with more weight. For example, Pisarenko only used 100k for good mornings, and that’s where I start with my RDLs. If one of the strongest men in history didn’t go beyond 225 lbs for his good mornings, then nobody here has any business doing so. I think RDLs should be used weekly (at the opposite end of the week from deadlifts) with a controlled weight for at least several months, and more like half a year (this would cap the weight in the 225 to 245 range for most people). After they have been employed consistently, then they can be used with heavier weights like Vlad did. It’s not that I dislike GMs, it’s that I like RDLs so much better.

guythepikey asks:

A quick question regarding the missing type of Squat the Overhead Squat, do you see it as a lowbar or highbar in terms of quads/glutes/hams utilisation?

Dear guythepikey,

I don’t see the overhead squat as something that will build strength and primarily see utility in it to help with the overhead rack position (side note: I never did or do them). To answer your question, it’s going to reflect high bar mechanics. Observe the question above with the Dolega example and you’ll see that the receiving position is in done with HB/front mechanics. Pushing the butt up on the overhead squat will only encourage forward inclination of the torso with a subsequent dumping of the bar forward. Any purposeful attempt to use low bar mechanics on the overhead squat is probably due to a lack of mobility (ankles, knees, hip flexors, external hip rotators, lumbar, thoracic, shoulders, etc.).