A couple of years ago I wrote “Low Bar vs High Bar Squat” and it is still one of the most visited, and argued, posts on this site. I re-read the post and felt the need to update some of the information.

In the first post, I compared the positioning, mechanics, and utility of the high bar and low bar squats. All bickering aside, my final recommendation on which squat to use was:

If you’re gonna be a powerlifter, then use the low bar. If you’re going to compete in Olympic weightlifting, then use the high bar. If you have deficiencies in one area, then the other squat can improve that deficiency. If you can do both reasonably well and aren’t training for one of the barbell sports, then use both.

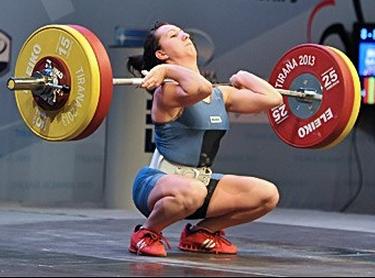

I do want to reiterate one point, and that is how the low bar squat should not be used for competitive weightlifting. Since weightlifting elements are common in CrossFit competition, I would also not predominantly use the low bar squat in CrossFit programming unless it was in the off-season. This is not any kind of attack on Mark Rippetoe or anyone who promotes the use of the low bar; the low bar is just not efficient for those purposes. Low barring will teach a trainee an inappropriate motor pathway for weightlifting as well as incorrectly developing the hip and thigh musculature.

To my knowledge I’m the one of the few people, if not the only one, who has gone to a USAW National event by primarily low bar back squatting. It definitely made receiving positions in the clean and snatch unnecessarily difficult as well as created mechanical problems (i.e. pitching forward when trying to squat out of the receiving position). After high barring consistently and dropping about 15 pounds of body weight, I was hitting the same PR snatch and CJ numbers with a weaker squat, and it was partially due to bettering the motor pathway of my receiving position and developing the musculature in a way that supports that pathway (The other variable of my improved numbers was that I significantly improved my weightlifting technique).

From a mechanical analysis perspective, it doesn’t make sense to low bar for weightlifting and it has not proved to be effective in my training or anyone I have coached. But enough about me, for gods’ sakes, let’s get to the amendments I have about the original Low Bar vs. High Bar article.

Hamstring tension during the high bar squat

In the first article I made a blanket statement saying, “the (high bar squat) ascent begins with zero hamstring tension due to knee flexion”. To review, if there is too much knee flexion, then there is not tension in the hamstrings since they cross both the knee and the hip. Yet, saying that all high bar squats have zero hamstring tension at the bottom position is not correct in all situations.

There are different ways to high bar squat. One method used by weightlifters is essentially collapsing into the bottom and allowing the backs of the hamstrings to slam onto the calves in complete knee flexion. The knees usually jut forward and some people say the rebound occurs off of the ligaments of the knees, though it’s probably a combination of the soft tissue around the ankles, knees and hips. The rebound off the soft tissue and joints is used as a rebound to drive the weight up. It’s similar to catching a clean or snatch very quickly. This can be called “ass to grass” or ATG squats. Another method is similar, except instead of crashing into the bottom position, the weight is lowered under control until the same bottom position is met. These are also referred to as ATG squats, but the weight is lowered under tension.

Lastly, the bottom position of a high bar squat can be a couple of inches below parallel, much like the low bar squat. To quantify this, the crease of the hip would need to be at a lower level than the knee cap (i.e. the point in which the head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum would be lower than the top of the patella). The weight would be controlled to this bottom position, and then squatted up.

While there is more knee flexion than in a low bar squat, there is not complete knee flexion and therefore not complete slackening in the hamstring. The hamstring is obviously much more slack than a low bar squat, but it will have some tension, especially when the trainee is externally rotating the hips effectively. External hip rotation effectively stretches out both the adductors and at least the medial hamstrings, therefore it creates tension around the hip. This is how I coach the high bar squat, especially with beginners.

All of the text in this section serves to show that I no longer think there is zero tension at the bottom of a non-ATG high bar squat.

Net anterior/posterior knee forces during the high bar squat

And all of the above text is important to make this point right here. Since there is adductor and hamstring tension applied in a non ATG high bar squat, these muscles apply a posterior force on the tibia. Therefore, the net force is not entirely anterior and therefore not as abrasive to the knees as originally thought. ATG squats will yield significantly higher anterior stress (i.e. the front of the knees), but ATG and regular high bar squats can still recruit hamstring tension on the ascent. If there is tension at the bottom of a non-ATG squat, and there is hamstring tension on the ascent (due to the hamstrings maintaining the back angle by their attachment on the pelvis), then the high bar squat can be excused from “knee wrecking” accusations.

In order to provide this tension the trainee would need to properly externally rotate at the hip, therefore making the high bar squat more difficult to master than I made it out to be in the first article when I said, “To learn how to high bar squat, put a bar on your back and squat all the way down with your knees shoved out.” A quality high bar squat will require good external rotation (to be discussed in another post and video).

The stretch reflex is still present in a high bar squat

Because there is hamstring and adductor tension at the bottom of a non ATG high bar squat, there is tension to execute a stretch reflex. The stretch reflex is one of the most important qualities of a low bar squat. Once a trainee starts mastering the low bar mechanics, I teach them how to “bounce” out of the hole with hip drive. The same thing can happen in the high bar squat, yet the intent and cues are different. Whereas in the low bar the trainee is aiming to “push the butt up” (a specific cue I found to be better than “drive the butt/hip up”), the high bar squatter will “drive the heels” while maintaining the external rotation.

Overall, the point in this section is to state that there is not complete knee flexion in a high bar squat, there is adductor and hamstring tension, and therefore there is a stretch reflex off of these muscles when coming out of the hole.

There is a difference

One issue that pops up occasionally is the idea that there is not a difference between the high bar and low bar. I guess the point is that there is not a mechanical difference, an adaptation difference, or that it doesn’t matter which one you do.

Some people may not have a noticeable difference in seeing or executing the two types of squat if they are a) very immobile, b) very uncoordinated, or c) squat with a wide-geared-powerlifting stance. Having crappy mobility would make it hard to see a difference between the two squat variants. Crappy mobility in the hips, knees, and ankles, would prevent a proper bottom position in a high bar. Crappy shoulder mobility would prevent a good rack in a high or low bar position (I’ve seen both). Therefore, when they attempt one or the other squat version, it just turns into a bastardized version of whatever their mobility permits.

The uncoordinated trainee may have the mobility to rack the bar or get into a bottom position, but he doesn’t have the coordination (or coaching) to execute the squat version.

Lastly, wide stance squatters aim to have vertical shins, sit back very far, and lean over to achieve hip flexion. This style of squatting — which I am not a fan of — developed in order to take advantage of gear that resists hip flexion (i.e. it helps extend the hips AKA squat up). Wide stance squatting relies on gear instead of good external hip rotation to provide force. Wide stance squatting will also look nearly the same regardless if the bar is placed on the traps (high bar) or on the rear delts (low bar), therefore there won’t be much of a difference between the two squats because the mechanics are the same anyway.

Despite the fact that large weights have been squatted with these wide stance squats, it doesn’t use the non-geared anatomy efficiently, is therefore more injurious, and is not conducive to athletics, weightlifting, or general performance. But I digress.

In closing…

I ended up talking a lot about the high bar squat and neglected the low bar squat. I just needed to revise and explain the above statements about the high bar. The low bar is still what I would coach for raw powerlifting, but if someone were interested in competing in weightlifting or CrossFit, then I would have them high bar. It would just depend on the individual, as usual. One thing we can all agree on…it’s better to have squatted than to not have squatted at all.

Justin, what cues do you use to coach the non-atg high bar squat?

It depends on how good (or not) that person already is at the movement. How much tightness they have in their trunk and in their hips.

I’m gonna do a post/video on this soon, but quickly:

1. Tightness in the trunk needs a) tension in the lower abdominals and b) chest up — note that these should be automatic with all barbell lifts, but casual lifters don’t focus on this.

2. Create tension on the hips with external rotation and abduction (kind of like spreading the floor) prior to beginning the rep.

3. Maintaining this tension throughout the entire rep.

4. “Heels” out of the bottom.

Couldn’t log in the other day for some reason, but I have some questions about my logic on the ungeared wide stance and why it may be useful. By using a wider stance, doesn’t this bring the feet further back posteriorly in relation to the hips when in the bottom of the squat? If you think about the legs as the hands of a clock, it would be the difference between the hands being at 11 and 1 with a narrower stance and 10 and 2 with a wider stance. At 10 and 2, the tips of the clock hands have less vertical distance to the center of the clock, as the feet would have less distance the hips in the anterior/posterior direction. The reason I think this whole thing is useful is that the feet being closer to the hips in that direction allow for a more upright torso when keeping the bar over the feet. This takes the lower back weak link out of the squat. It also takes some tension of the hamstrings like high bar vs low bar as well, but wouldn’t it also bring the adductors more into the movement to compensate? I’m not an anatomy guy, just learning all this stuff.

The other reason I think the wider stance might be useful is that as you said, it allows for more vertical shins. The effect this should have other than the one you addressed is that it makes the top of the knees higher up, and the hips don’t have to drop as low to break parallel. Wide stance also drops the starting/lock out position of the bar a bit. Between these two things, a wide stance squatter should have less distance for the bar to travel between breaking parallel and locking out, correct?

Pingback: Monday 8/11/14 - Member Profile: Tyler Trick

Pingback: External Hip Rotation in the Squat | 70's Big

Great followup Justin. Would low bar be most beneficial for someone with meniscus problems? I had some of the lateral meniscus removed, and I’m wondering what style would be most beneficial for me. I’m thinking the low bar balances the shearing forces between the tibia and femur better than the high bar?