In “Shoulder Health – Part 1” I reviewed the musculature surrounding the shoulder and body posture. Posture is important because it dictates shoulder mechanics, specifically internal and external rotation.

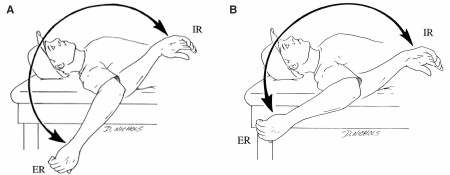

Shoulder rotation is easy to decipher: if the anterior aspect (front) of the humerus (upper arm bone) rotates medial (towards the middle of the body), that is internal rotation. If the anterior aspect rotates laterally (away from the middle of the body), then that is external rotation. This holds true regardless if the elbow is flexed or extended, or if the shoulder is flexed, extended, abducted, etc. For example, put your arms overhead. Turn the front of your biceps (which sit on the anterior aspect of the humerus) towards your ears; this is internal rotation. Now turn them back and to the outside, and this is external rotation. Coincidentally this external shoulder rotation while in flexion is what the training community refers to as the “overhead position” — which is the position in which a person can bear a load safely (i.e. with good mechanics).

But it’s important to understand why external rotation facilitates a good overhead position and is the basis for shoulder stability in all shoulder movement. There are several reasons that are intimately related: shoulder positioning, muscular involvement, and force distribution (or mechanics).

Shoulder Positioning

Simply put, external rotation keeps “the shoulder” back and down whereas internal rotation moves it forward. “The shoulder” is actually the articulation of the humerus into the glenoid fossa; this junction is collectively called the “glenohumeral joint”. This bony articulation will be the focal point when we observe if the shoulder is “back” or “forward”. Keep in mind that the glenoid is a part of the scapula, or shoulder blade, and scapular movement (up, down, in, or out) can influence shoulder position.

External rotation on the left, internal rotation on the right. Note the change in position of the glenohumeral joint. (I took the flannel off for clarity)

In the above picture, the shoulder is in neutral position (relative to anatomical position), and the elbow is flexed. But you can see this same glenohumeral movement even in extension or flexion (i.e. if your arms are overhead for shoulder flexion, you can see the glenohumeral joint move if you completely internally rotate compared to where they were in complete external rotation).

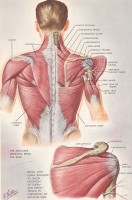

This forward transition in internal rotation completely changes how the shoulder receives and distributes force (which we’ll talk about in the next two sections). But it also has an effect on thoracic spine positioning. The scapula is primarily held in place by the trapezius muscles and the rhomboids (see image right). So if internal rotation occurs, it pulls the scapula laterally to pull on those muscles that anchor the scapula. The result is that if the shoulder is in severe internal rotation, the thoracic spine cannot achieve quality extension.

This is easily seen in poor front squat or clean mechanics in CrossFit or Olympic Weightlifting. When the trainee flares their elbows out to the side (internally rotates the shoulders), their chest inevitably falls to round the upper back and usually also causes the lumbar spine to round (which may be directly caused by the thoracic spine or caused by the hip impingement from not shoving the knees out to externally rotate the hip). This severely inhibits good front squat mechanics and results in the trainee not training their musculature properly (it doesn’t work the upper back muscles, it shifts the center of mass forward, puts most of the weight and force application into the knees, and removes the gluteals and even the hamstring involvement, and undoubtedly contributes to “The CrossFit Quads“). The cure for this is to cue the elbows “up and in”. “Up” means shoulder flexion and “in” means external rotation in the front rack. This cue should be distributed en masse to all CF facilities.

Hard to find a good example, but flared elbows means internal rotation means flexed thoracic spine means ineffective exercise.

Glenohumeral positioning has an effect on thoracic extension. Furthermore, having limited mobility in the shoulder is compensated by the thoracic spine. Let’s assume a person that has a poor overhead position. They cannot achieve full shoulder flexion (straight up and down) much less do it with external rotation. Their straight arm is five degrees forward of vertical (example). In order to put the bar “overhead”, they will compensate by hyper extending their thoracic/lumbar junction by 5 degrees (see image right). This is bad for several reasons: 1) places undue stress on the thoracic/lumbar junction or the lumbar/sacral junction; 2) it caters to existing shoulder or hip immobility and makes it worse; 3) it does not allow the trunk muscles to properly stabilize or develop properly which 4) results in a lack of progress and strength development in the press and 5) probably leads to some sort of injury or irritation, whether it be in the shoulders or cervical/thoracic/lumbar spine.

Glenohumeral positioning has an effect on thoracic extension. Furthermore, having limited mobility in the shoulder is compensated by the thoracic spine. Let’s assume a person that has a poor overhead position. They cannot achieve full shoulder flexion (straight up and down) much less do it with external rotation. Their straight arm is five degrees forward of vertical (example). In order to put the bar “overhead”, they will compensate by hyper extending their thoracic/lumbar junction by 5 degrees (see image right). This is bad for several reasons: 1) places undue stress on the thoracic/lumbar junction or the lumbar/sacral junction; 2) it caters to existing shoulder or hip immobility and makes it worse; 3) it does not allow the trunk muscles to properly stabilize or develop properly which 4) results in a lack of progress and strength development in the press and 5) probably leads to some sort of injury or irritation, whether it be in the shoulders or cervical/thoracic/lumbar spine.

Now you should have a good understanding that internal rotation and/or lack of shoulder mobility can influence the positioning of the glenohumeral joint, but also the spine when lifting.

Muscular Involvement

Look at the image of the posterior shoulder anatomy again. Review the video from part one. We already know that the shoulder is the articulation of the humerus with the scapula. We know that rotation of the shoulder can alter the positioning of this joint. and we also know that since the scapula sits on the back of the rib cage, most of the musculature holding it in place is on the posterior side. There are some muscles that attach on the anterior aspect of the shoulder, but most of the important muscles are posterior. Also keep in mind that there is not a lot of structural stability in this joint — the muscles that attach around the glenoid and the head of the humerus hold everything in place. When you make a fist, your have some tissue surrounding a lot of bones. Your shoulder is pretty much two bones touching with a lot of muscles wrapped around it.

I point the anatomy out, because how these muscles are used matters. Previously mentioned muscles like the traps or rhomboids will effect scapular positioning, but the health of the shoulder joint lies with what people call “the rotator cuff” muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. Other muscles like the teres major and lattisimus dorso play vital roles in shoulder mechanics.

The point isn’t to learn all of these muscles, but to the general role that shoulder musculature plays, especially regarding lifting. Some muscles externally rotate while others internally rotate. We already know that external shoulder rotation is efficient and desirable, but the muscle action supports this.

Without good coaching, a trainee will perform a press, bench press, or push-up however they can. They’ll utilize existing musculature to try and get the job done. But internally rotating the shoulders leaves out a lot of musculature, and thus stability in the shoulder. By externally rotating, all of the muscles that externally rotate will contract and all of the muscles that internally rotate will lengthen with tension. This last part is important, because in a well excecuted bench press the internal rotators will be taut and help stabilize the joint. In the same way that the hamstrings lengthen with tension during a squat, the internal rotators will be stretched, yet apply lots of tension to play their role in holding the shoulder in place.

On top of this added stability, the proper external rotation in this bench press also allows the distribution of force into other muscles (like the pecs and triceps) without exposing an area or structure to undue injurious stress. In other words, by using external rotation in pressing and pulling movements, more musculature is being used properly, which helps a trainee get stronger. This is also why people who internally rotate (and flare their elbows) will eventually experience pain or injuries. For example, conventional powerlifting lore says that pressing overhead is bad for the shoulders — and they are right! If you press overhead with crappy mechanics, you should expect to destroy your shoulders.

Force Distribution

I use the term “force distribution” to refer to what muscles are being utilized in a given movement. By lifting with quality shoulder positioning and mechanics, the muscles around the shoulder work in symphony to apply force. Proper technique yields comprehensive muscular action and development. I use the phrase “even force distribution” to mean that one muscle or muscle grouping is not solely relied on to complete a movement, and instead it is distributed evenly across all of the muscles that are supposed to be used.

For example, above I critiqued the poor CrossFit girl’s front squat technique (she needs lifting shoes too). By flaring her elbows on her front rack she drops her chest to a) round her upper back and b) drop the bar forward on her shoulders. When the bar shifts forward, it moves her overall center of mass forward, and then her knees and quads receive the brunt of the responsibility to stand up with the weight. In a quality clean or front squat, the load will stay centered to allow all of the muscles of the thighs and hips to apply force. In this case all of the gluteals, the hamstrings, and her lateral quadriceps are not contributing to the movement. Whether she’s doing the front squat for strength or conditioning, her coach is letting her not train her musculature as efficiently as she could. A crime, really.

Back to shoulder anatomy. If internal rotation occurs on pressing movements, then force is unevenly distributed. Specifically, the acromioclavicular joint (where the tip of the shoulder meets the clavicle) receives a lot of stress. This is also the same region as the proximal biceps tendon and the insertion of the supraspinatus. This means that these two tendons (biceps and supraspinatus) are often irritated, strained, and later frayed or torn when bad mechanics are used chronically.

In order to have even distribution across the shoulder muscles we must have good shoulder positioning, and this is done by using proper external rotation with respect to the exercise being performed. Good position allows for the proper muscles to act not only in the way they evolved to act, but in symphony with each other (this is an important point that is the reason that compound, multi-joint exercises are optimal for strength training and rehab). Since the positioning and musculature are correct, the force application is evenly distributed so that the muscles do their job, keep the joint safe, and get stronger.

The problem is that all of this is either inhibited or not possible with crappy shoulder mobility. And that is the topic in Part 3.